The amazing ‘Conference’ pear

It took a blackbird to teach me how good the ‘Conference’ pear is. For several years after planting it I thought it was hopeless. The fruit was rock hard and almost tasteless. I gave up on it and just left it unharvested.

And then one November morning I noticed through the kitchen window a blackbird on a branch feasting on one. It had the look of an addict being given a fix as it bit into the soft fruit in a frenzy of desire. Stop there. What did I just say? “Soft?”

I ran outside and picked one. The interrupted bird hopped on to the nearby trellis, staring with jealous fury. I bit into it. Soft and sweet. Oh, so sweet!

Since then I’ve left the blackbirds to judge when it’s time to pick – always when the leaves are falling, which is what had deceived me into picking them too soon.

As reward for their service we have negotiated a deal. I make sure to leave some behind.

Award-winning pear

It was the history of this pear that first drew me to it.

Back in the 1880s the British fruit industry was struggling. A dramatic reduction of duties on fruit imports in 1837 and the rapid growth of the railway network had let in fierce overseas competition. French growers were soon taking a big bite out of the London market.

“By repealing the duty on foreign fruit, they rendered valueless the orchards which had taken all my life to raise and upon which I have expended large sums of money” – William Harryman, Kent farmer Maidstone Journal 1841

The French had the advantage of warmer weather. Prized varieties like ‘Williams’ Bon Chrétien’ ripened earlier there, commanding a premium price in England. And they were able to grow late season pears at a time of year when these pears were thin on the ground in British market gardens.

In her excellent The Book of Pears, Joan Morgan records how the French sent their boxes over – the fruit carefully wrapped in tissue paper, with shredded paper between the layers to prevent bruising. In the winter the boxes would be wrapped in extra layers of cotton wool.

Refrigeration

Refrigerated steamships (and railways offering discounts to importers to win business from the ports) meant that soon the Americans and Canadians were piling in, too.

The British needed investment. Most commercial orchards were small-scale market gardens. Their owners had probably trained in large private gardens where it was common to have dozens of different varieties, supplying the cook and owners with fruit for much of the year.

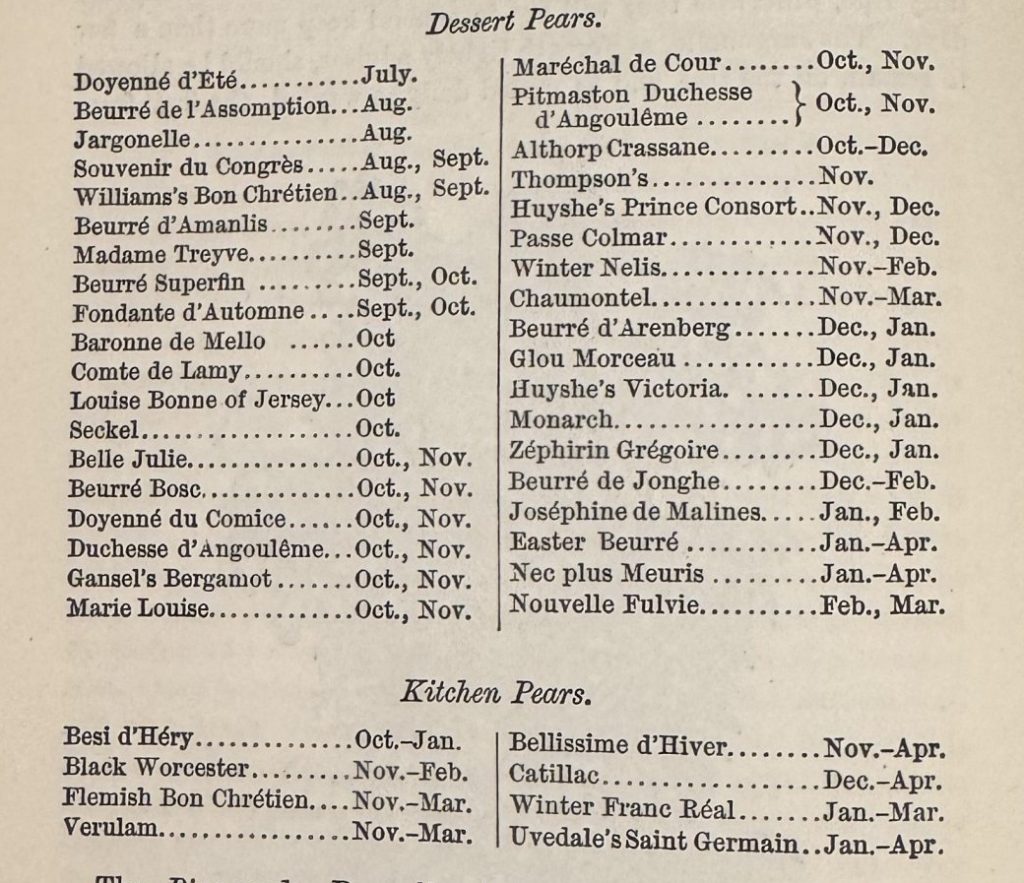

The Epitome of Gardening, written in 1881, demonstrates how with clever planting these gardeners could extend the season. It would start in July with ‘Doyenné d’Eté’. And go on deep into winter, with ‘Joséphine de Malines’ in January and February, ‘Nouvelle Fulvie’ from February to March and ‘Easter Beurré’ and ‘Nec plus Meuris’ cropping from January to April. (Note how many of these names are French, indicating where the leaders were in this field.)

The authors suggest an old gardener’s trick of picking the first fruit from each tree a fortnight or more before ripe, the second a week or 10 days after that and the third when fully ripe.

“The first gathering will come into eating latest and thus the season of the fruit may be considerably prolonged.”

All of this meant that there were just a few weeks in spring when the table would go without pears.

That was fine for stately homes but if you wanted to grow commercially and compete with the French then you needed far fewer varieties and good ones. But which?

Pear conference

In 1885 the Royal Horticultural Society staged a National Pear Conference at its gardens in Chiswick, London, to identify the best for growing in the UK. Nurseryman T. Francis Rivers opened the event saying:

“We must plant on a different principle to that of our forefathers… Instead of the acre of grassland with the customary 108 trees often broken down by livestock, and producing more wood than fruit, the modern orchard must be condensed into a compact compass to give more fruit in one rood of land than in two or three acres in the old-fashioned style.”

Growers submitted 615 pear cultivars to be judged. The committee recommended which to grow for each county (a great resource if you’re looking to plant a heritage variety in your garden). Of the new pears one stood out. It was the only pear awarded a “First Class Certificate as a market variety”. It was the ‘Conference’ pear, and we’ve already met its creator – T. Francis Rivers.

The Rivers nursery

The Rivers nursery in Sawbridgeworth, Hertfordshire, was founded in 1725 and operated continuously through to 1987. Francis’s father was the legendary Thomas Rivers (1798-1877) who in his early career had been a keen a rosarian (we’ll meet him in more detail soon!).

By the 1850s Thomas had moved on to fruit trees and become a key figure in the world of pomology. He introduced the ‘Early Rivers’ plum, which extended the fruit season (and is still one of the earliest plums). In 1854 he helped found the British Pomological Society. He worked on developing smaller fruit trees that were more compact.

So Francis had had a good education. He introduced a number of fruit cultivars himself, but it is the ‘Conference’ pear for which he is most famous. The female parent was a Belgian pear, Leon Leclerc de Laval. The male parent is unknown. In the company catalogue of 1897/98 ‘Conference’ is described as:

Fruity large, pyriform; skin dark green and russet; flesh salmon coloured, melting, juicy, and rich. Tree robust and hardy. Very prolific, a good garden and orchard fruit, and a valuable market sort. November 1st to third week.

The tree was also self-fertile and scab resistant. Its popularity spread. Morgan tells us that by the 1890s it was the universal English pear. It may not have cropped all year round but it was “in season during the profitable autumn months when England’s harvest could triumph over imports.”

Fruit hero?

Did the ‘Conference’ pear save the British fruit industry? It helped! A series of poor harvests from about 1880, competition from cheap American wheat and outbreaks of foot and mouth disease (spread by imported cattle) and bovine tuberculosis meant farmers were looking for alternatives.

Many turned fields over to efficient, large-scale orchards – with gooseberries, blackberries and strawberries grown between the rows of trees. The expansion of the South Eastern Railway network into Kent meant farmers there could once again compete with London’s market gardeners and the French. Between 1873 and 1898 Kent’s orchards and strawberry fields more than doubled from 10,161 acres to 25,050.

For a while, at least, Britain became a serious fruit producer. The ‘Conference’ pear played its part and still does. An orchard census in July 2025 by the British Apples & Pears fruit grower organisation showed that there are 1 million pear trees in commercial orchards in Britain today. Ten varieties of pear are being grown commercially and ‘Conference’ accounts for 93% of the crop.