Who was Mme Grégoire Staechelin?

A couple of years ago I went on a rose pilgrimage to Barcelona to meet one of that country’s greatest rose breeding families – the Dots. I was particularly keen to learn more about the founder of the dynasty, Pere Dot, because he bred one of my favourite roses, ‘Mme Grégoire Staechelin’. I wanted to know who the rose is named after.

Mystery has always surrounded it. Some authors have said Mme Grégoire Staechelin was the wife of a Swiss ambassador in Madrid. I can find no mention of a Staechelin on the ambassadorial staff there in the 20s when the rose was bred.

Roger Mann, in his 2008 book, Naming the Rose, claims the woman was Dot’s friend and this was a wedding gift to her. He tells how a Swiss friend had an uncle at the University of Basel in the early 1930s. One of the medical professors was Dr Grégoire Staechelin. His lectures, it is said, were tedious but students crowded into them hoping for an invitation to lunch with his charming and very beautiful Spanish wife.

Roger Mann, in his 2008 book, Naming the Rose, claims the woman was Dot’s friend and this was a wedding gift to her. He tells how a Swiss friend had an uncle at the University of Basel in the early 1930s. One of the medical professors was Dr Grégoire Staechelin. His lectures, it is said, were tedious but students crowded into them hoping for an invitation to lunch with his charming and very beautiful Spanish wife.

Behcet Ciragan from Switzerland claims in an article he wrote in 2019 that the Staechelin we are looking for is Gregor Staechelin (1851-1929) – a prosperous building contractor in Basel. And if that is the case, then Mme Staechelin was his wife Emma, née Allgeier (1859-1941).

Pere Dot’s grandson did not have any answers, but in Barcelona Dot’s biographer, Jaume Garcia i Urpí, told me the idea for the naming came from Dot’s French mentor, Jean Claude Forestier (1861-1930). So I followed two trails – one in France and one in Switzerland – to dig further.

Bagatelle

Before the First World War, Dot (1885-1976) worked in the Bagatelle gardens in Paris under Forestier, its legendary creator. It was there that he learned to hybridise roses. Forestier created the first rose trial beds there in 1907. Dot worked on these beds, seeing the latest varieties and meeting the breeders who created them.

When war broke out he returned to Spain and began rose breeding, maintaining his connection with Forestier. He entered his first rose in the Bagatelle trials as early as 1924, winning a certificate of merit for ‘Margarita Riera’.

Mme Grégoire Staechelin

‘Mme Grégoire Staechelin’ and another superb Dot rose, ‘Nevada’, were launched in 1927. That year ‘Mme Grégoire Staechelin’ won a gold medal in the trials at Bagatelle.

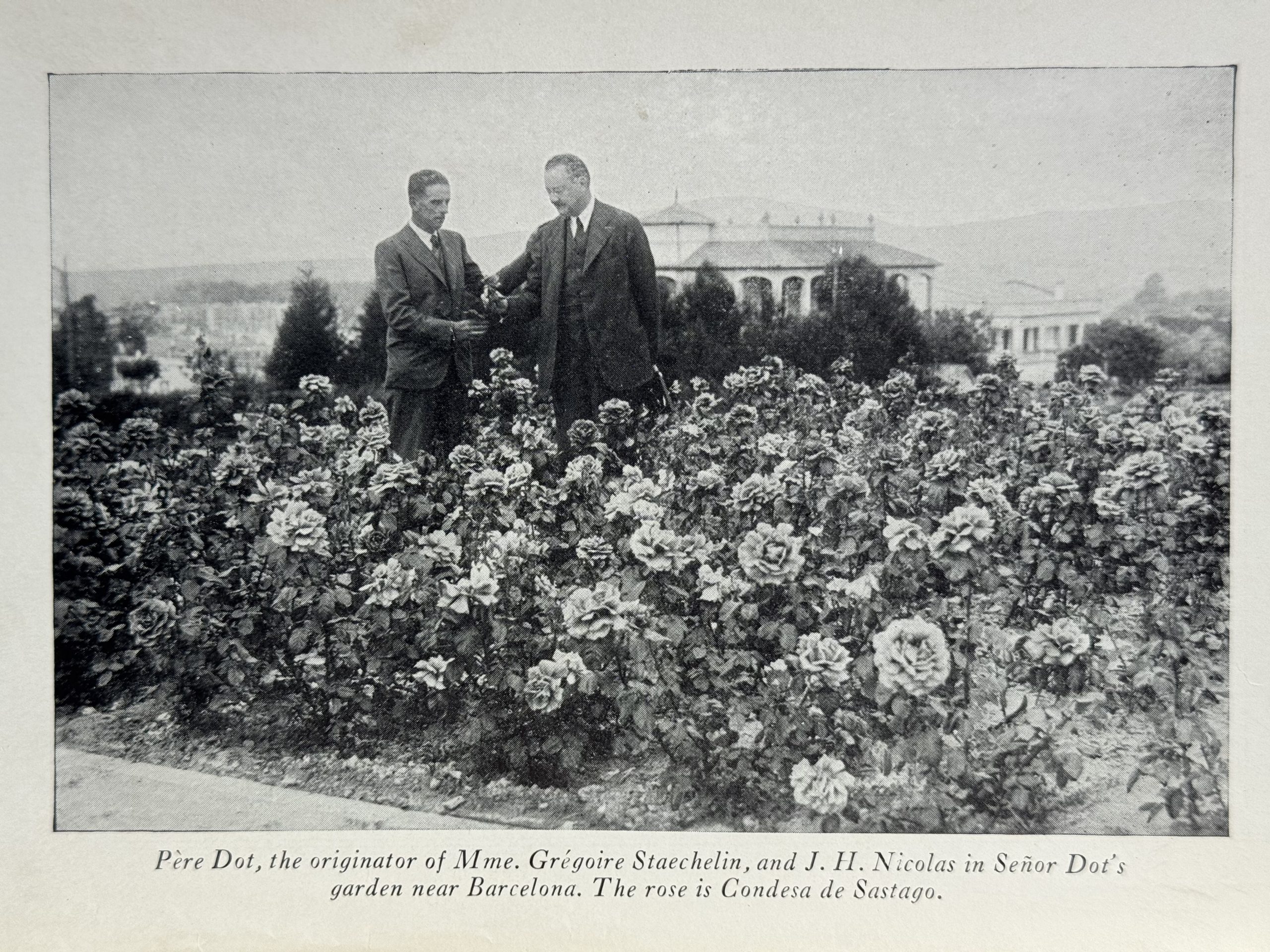

An article in the 1931 American Rose Annual by Jean Henri Nicolas confirms that the Bagatelle connection is crucial to the naming story. Nicolas, a Frenchman usually known as J. H. Nicolas, was a rose breeder who worked for the famous Conard-Pyle nursery in Pennsylvania. He was always looking out for great European roses his company could sign the US distribution rights for. In fact, he was a judge at Bagatelle. Nicolas tells us that it was Forestier who took the credit for naming the rose.

“At Bagatelle, I met my old friend J. C. N. Forestier… retired superintendent of the parks in Paris… [who said] ‘I named that rose for Mme Staechelin.’ I saw Pedro Dot, who… informed me that in Spain the rose is known as “Stahklin” (in Spanish, ch is sounded as k.) and I found it so everywhere in Europe.”

Early reputation

Nicolas had a special interest in this astonishing new rose. A Pennsylvania newspaper[1] in 1929 tells how he was at a banquet in Paris when he first heard of it – perhaps before it was being widely sold.

“He took the train that night to go in search of it. When he came to the Pyrenees mountains, which divide France and Spain, he found he had just missed the little shuttle train, which took passengers through a three-mile tunnel to the Spanish train. He thought he could catch it by walking through the tunnel and engaged a man with all the earmarks of a mountain brigand to guide him through. His money had all been changed into the heavy silver coins of Spain at the customs house and at each step his bulging pockets clinked.”

The tunnel was so dark the guide held the brave rose breeder by the arm and tapped the rails as they went along with a large club. Nicolas breathed a sigh of relief when a spot of light appeared at the end of the tunnel. He figured that..

“…as long as the fellow had not brained him when the opportunity was ripest, he probably would not do it then. The final stage of his journey in quest of the lovely Spanish rose was made on donkey-back, five miles up into the mountains. When he reached the end, saw the rose and found he could get it, he felt that all his trouble had been worthwhile.”

Forestier

Conard-Pyle continued to market Dot’s roses in the US and helped to keep the business afloat during the Spanish Civil War.

It seems plausible that Forestier suggested the name – he is known to have done the same for another great rose, bred by Eugène Turbat in 1916, ‘Ghislaine de Féligonde’.[2]

So was Forestier friends with the Staechelins in Switzerland? They were a wealthy family and probably well-connected. Gregor and Emma celebrated their golden wedding anniversary in 1927 – the year the rose was launched. Could Forestier have suggested the naming as an anniversary gift? Or was he friends with their son Rudolf (1881-1946)? Rudolf made his fortune in real estate. He is famous for amassing a fine collection of impressionist paintings, including several Picassos. Next stop Switzerland!

Staechelin family

When I find their great-grandson, Ruedi, he is no doubt as to the provenance of the rose’s name. He says: “I am quite convinced that this rose was named in honour of my great-grandmother. Our family has always known about the rose. It has always been part of our family story and it has been planted in the garden of every house I’ve lived in.”

He adds: “Gregor Staechelin was a self-made man. He was a German immigrant from just across the border who started work building houses and then became an architect. Gregor became quite a wealthy man. He was a Catholic, which was not so good in a Protestant city like Basel. But nevertheless, he got on well and even won election to the local canton council.”

Gregor Staechelin wrote a book about his family history, published just after his death. It does not mention roses, says Ruedi. But in it are two rare photographs of the couple. So the connection to Dot is unproven, but looks to be correct. And that being the case, we now know not just who Mme Staechelin was, but also what she looked like.

Superb rose

The rose itself is stunning. It is one of the first to bloom in my Nottingham garden. It starts out from an elegant, long, pendulous crimson bud. I describe it as a pout. But if it is a pout then let’s say what follows as the rose unfurls is not the sort of peck on the cheek you’d get from an elderly aunt. Others have described the full bloom – 13 cm across – as like a flamenco dress in full flow.

The flower is followed by one of the biggest hips I know – orange-pink and pear-shaped. In the US ‘Mme Grégoire Staechelin’ goes by the name “Spanish Beauty”. I saw it under that name in a garden in Japan recently, too. It is a good description. It only blooms once, but what a display. I hope Mme Staechelin liked it, too.

With thanks to French garden historian Vincent Derkenne for supporting research.

[1] Daily Local News (West Chester, Pennsylvania) Wed 5 June, 1929

[2] Madeleine Mathiot in an article for the Bulletin de Roses Anciennes en France 2005 from a member of the de Féligonde family.