UK Rose Society at 150

As he tells it, it all started with an English vicar walking into a bar. It’s the early 1850s. Samuel Reynolds Hole, vicar of the village of Caunton, receives a telegram from nearby Nottingham inviting him to judge an Easter rose show.

He thinks it is an April Fool’s joke. No-one grows roses in April. But, intrigued, he climbs aboard the train to Nottingham, footwarmer and blanket in hand.

At the General Cathcart Inn a mob of horny handed labourers greet him and tell him the roses are ready for him to judge upstairs. What follows is a Damascene experience. “A prettier sight, a more complete surprise of beauty, could not have presented itself on that cold and cloudy morning,” he later wrote in his incredibly popular A Book about Roses.

He was transfixed. At the end of the day Hole was sent home clutching a bouquet. Within a week he had placed his first order of a dozen roses. Before long, well, you probably know the feeling.

“Year by year my enthusiasm increased. My roses multiplied from a dozen to a score, from a score to a hundred from a hundred to a thousand, from one to five thousand trees. They came into my garden a very small band of settlers, and speedily, after the example of other colonists, they civilised all the former inhabitants from off the face of the earth. They routed the rhubarb, they carried the asparagus with resistless force, they cut down the raspberries to a cane. They annexed that vegetable kingdom, and they retain it still.”

In truth, Hole was just telling the story for effect. It certainly helped him sell lots of copies of his book – by the time of his death in 1904 A Book about Roses had run to 19 editions and been published in the US and Germany. And it helped make rose growing and showing popular in Britain.

A grand national show

But research shows Hole had actually been growing roses for 20 years and this all happened in 1860 – two years after a much more important show took place (explaining why he was invited to judge).

In April 1857 Hole had suggested in The Florist, fruitist and garden miscellany magazine the idea of a GRAND NATIONAL ROSE SHOW. He waited with bated breath for a response. When none came he wrote to the country’s leading rosarians – Rivers, Paul and Turner – to ask if they would help him. To Hole’s delight, all three wrote back quickly in assent.

“I remember that in the exuberance of my joy I attempted foolishly a perilous experiment, which quickly ended in bloodshed – I began to whistle in the act of shaving.”

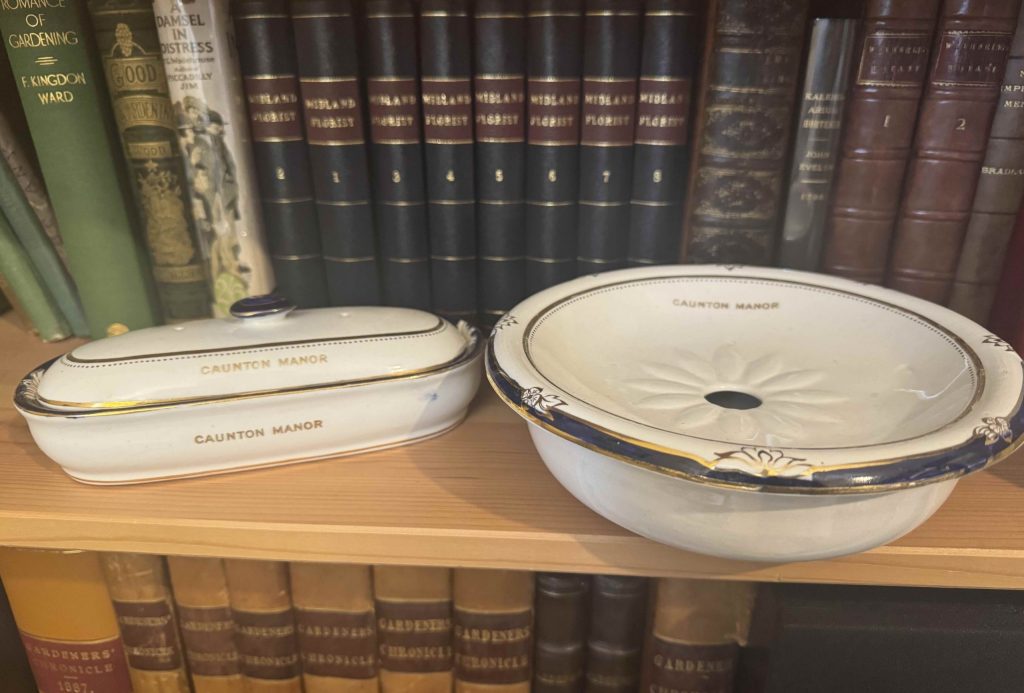

I once gave a talk on Hole in Caunton and afterwards someone presented me with his shaving soap bowl and razor blade dish. They are among my most prized possessions!

Standing at the entrance on the day of the exhibition Hole was understandably nervous.

“Would the public endorse our experiment? Would the public appreciate our Show? There was a deficiency of £100 in our funds for the expenses of the exhibition were £300; and as a matter both of feeling and finance I stood by the entrance as the clock struck two, anxiously to watch the issue.”

More than 2,000 “shillings” came. The event was a success, but that high-wire finance act was to become a recurring motif in this story.

Launch of the National Rose Society

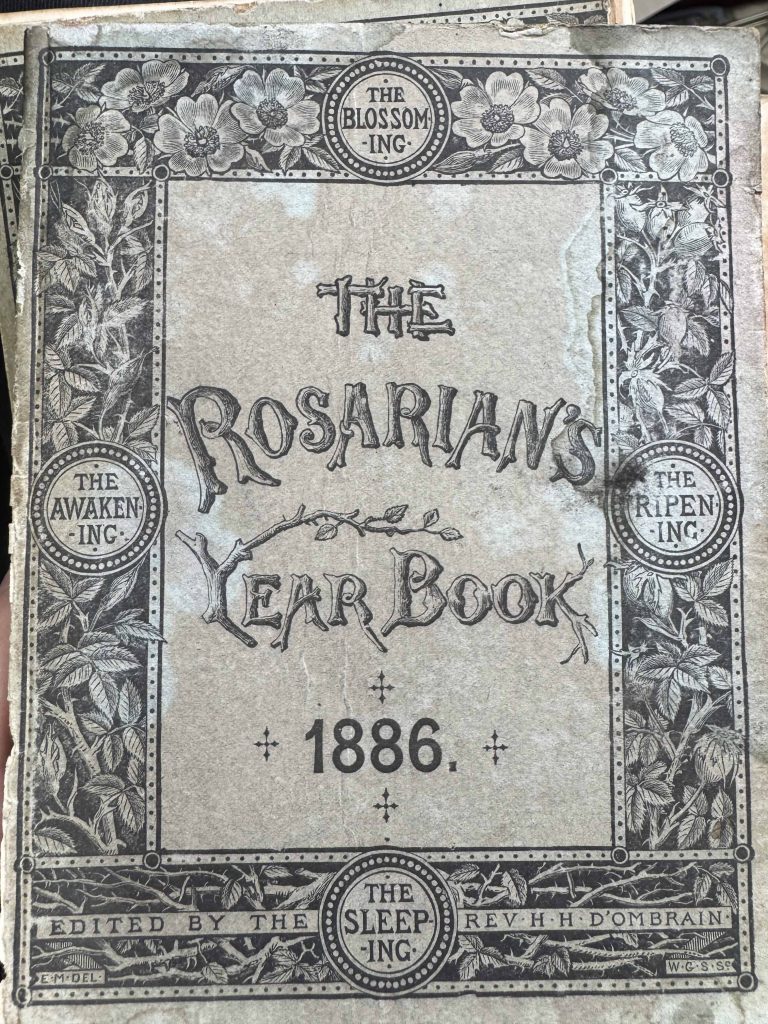

By 1876, the show had become a two-day event and standards had slipped, with exhibitors focused on quantity over quality. Enter another vicar. Under the auspices of the Rev Henry Honeywood D’Ombrain (1818-1905), the National Rose Society was established, taking over the running of the National Rose Show.

The first meeting of the Society took place “on a murky December day in 1876”. Hole, by now Dean of Rochester, was there and agreed to become its founder President. So were three more vicars (if I could be reincarnated backwards, I’d like to be a Victorian vicar with a healthy stipend and a big garden, please). The meeting was graced with the company of some of the great nurserymen of the time – Rivers, Paul, Cant, Laing and Turner.

The first show they organised was a financial disaster. Only members of the Society and their friends came. Writing up the account in the Rose Annual of 1926, the Society’s then deputy President, Haywood Radclife Darlington, wrote:

“What was to be done? Was the whole scheme to be abandoned? The universal cry was in the negative, the prize-winners consented to take a portion of their money, and to wait for better times for the balance.”

With the chief prize in the Amateur Division being a 50-guinea cup (worth about £5,000/US$6,700 in today’s money), it is perhaps not surprising they found themselves in debt.

Taking root

In recognition of the fact that this was a National Rose Society the first metropolitan show was organised, in Manchester in the Northwest. More regional shows followed.

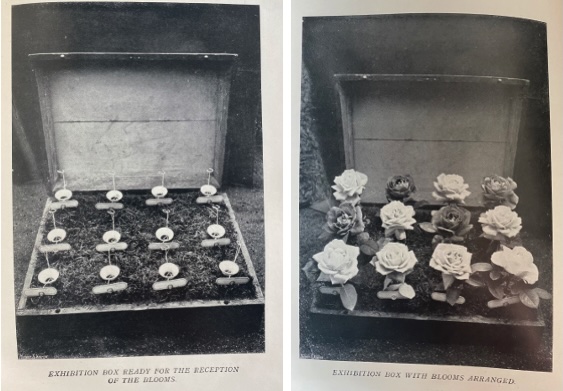

For many years the roses were shown in rigid boxes “tightly upheld by wires or other supports and staged in serried lines”. People complained that the rose was not being shown to best advantage. And it meant the focus was all on the size of the flower.

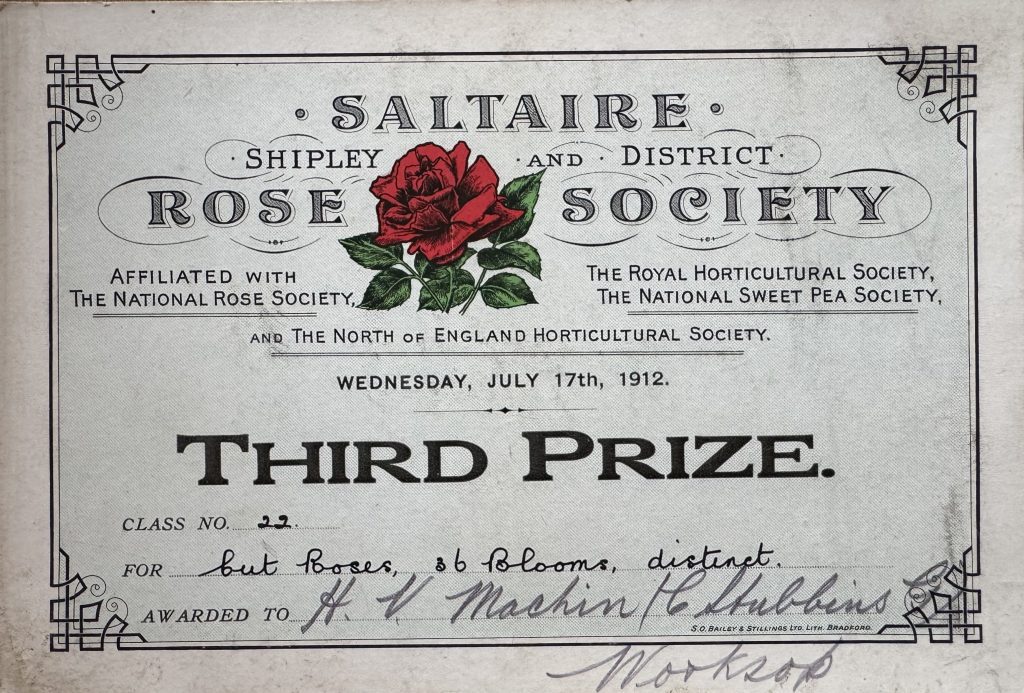

Innovations were to come. After heated debate it was agreed in 1892 that exhibitors be grouped by how many roses they grew, so as not to pit some amateur with a modest garden against someone like gentleman farmer H. V. Machin, who grew 50,000 roses just for showing and had several staff. Classes were introduced for a “display of roses” and more attention was paid to garden roses.

The Society became more focused on using the shows to encourage people to grow roses and not just compete with them.

Soaring membership

These innovations meant that by 1925 35,000 visitors attended the show in London. The Society’s membership grew, too – to 4,500 by the outbreak of war in 1914 and 13,000 by 1926.

The Society inspired rose growers around the world to form similar organisations.

In 1963 the Royal National Rose Society Trial grounds opened in St. Albans. In 1965 the organisation became the Royal National Rose Society, with the Queen as its patron. At that point the society had nearly 105,000 members. It peaked with 118,450 in 1968 when membership fees were doubled – from 10s6d to £1. That decision cost the society 15,000 members in one year. It was downhill from there.

By the early 2000s the garden at St Albans had become rather antiquated and neglected. After a fundraising effort it was closed to the public in 2005, razed and completely redesigned. It was reopened in 2007 with a more contemporary design featuring 20,000 rose bushes with mixed companion planting. The garden was beautiful, but insufficient attention was paid to keeping costs down, understanding pension liabilities and in engaging effectively with members. The Society had a staff and even its own wine club.

Bust

In May 2017 the Royal National Rose Society was declared insolvent. Bailiffs moved in and the garden was permanently closed. The world’s oldest specialist plant society seemed dead.

That it found a new life, was largely down to the efforts of three people – Ray and Pauline Martin and John Anthony. The organisation was resurrected just a few days after its downfall as the “Rose Society UK” and recognised by the WFRS. In an era when member organisations all struggle for numbers, today’s new Society has grown steadily to approaching 1,000 members. Subscription is just £10, meaning it attracts members from around the world.

That £10 offers you free access to a winter webinar series, publications (the committee are currently looking at ways to enhance the approach to content), a couple of events each year – special garden tours and pruning workshops etc. – free entry to shows for exhibitors and also discounts from rose suppliers. The Society is a valuable source of expert advice and support to all rose growers.

It is a battle to keep organisations alive in a digital age when people are bombarded with content. The UK Rose Society is unlikely to ever see 100,000 member subscriptions again, but it has re-rooted, and, thanks to the good guidance of a small number of enthusiasts, is growing healthily – an attractive shrub rather than a virulent climber! Happy 150th birthday!

Top photo: Image: RNRS Rose Society Garden at St Albans, CC BY-SA 3.0