Who was ‘Alister Stella Gray?’

There’s a famous Johnny Cash song – A Boy Named Sue – about a cruel father who christens his son “Sue”. He then deserts his family, leaving the child to a lifetime of bullying. Years later Sue tracks down his father in a bar. A fight follows and at the end Sue asks his father why he gave him the name. The answer is that it was to make him tough.

I can’t help thinking of that song whenever I see this rose. Its creator, Alexander Hill Gray, gave his son, Alister, the middle name “Stella” and later named the rose after him. But why?.

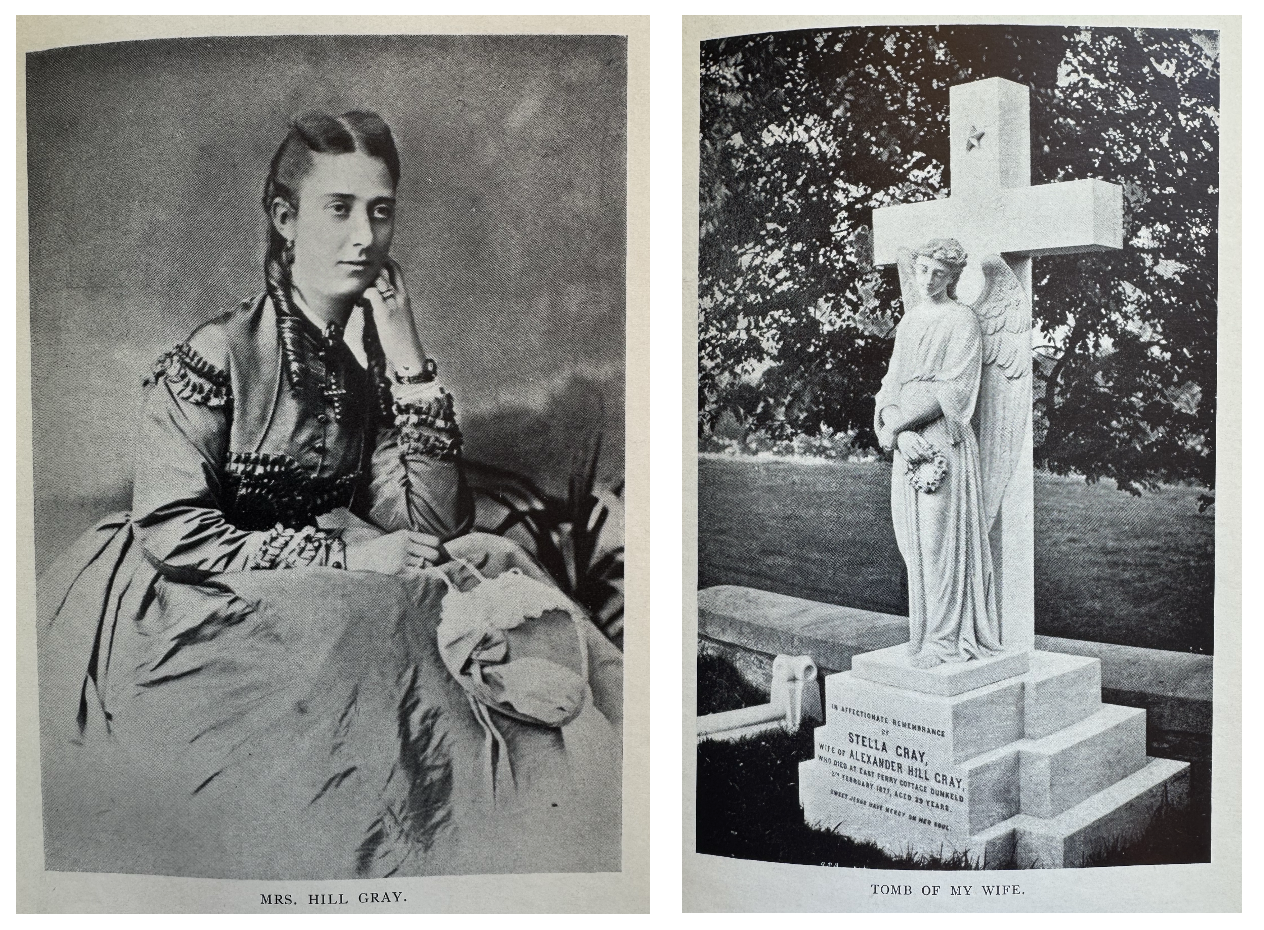

Alister Stella Gray was born in Dunkeld Scotland, in 1877. His mother died of septicaemia just three days later. She had been born Marcella Kerr but converted to Catholicism on marrying Alexander, taking her name “Ella” and changing it to “Stella”. That’s the name grief-stricken Alexander had carved on her tombstone.

So, Alexander named his son as a memorial to his late wife – a habit, I’m told, that is not uncommon in some Catholic countries. Did it make the boy as tough as his father? That was a high bar to jump. Because Alexander Gray Hill was one of the great adventurers of the Victorian era.

In 1925, then 88, he wrote a book about his dangerous travels as a young man.

Sixty Years Ago – wanderings of a Stonyhurst boy in many lands reads like a Rudyard Kipling colonial adventure.

Alexander’s birth

Alexander was born at Government House in Calcutta (now known as Kolkata) in 1837. At the age of five, he and his brother – then not-quite-four – were shipped to England. They were sent to a preparatory school for Stonyhurst – a Catholic boarding school in Lancashire. He wrote:

“When I look back on those days, I feel some pity for those two poor little mortals snatched from a mother’s care and from all female society at so tender an age.”

His own mother died just a couple of years later. Alexander moved on to Stonyhurst. It was tough. Like many ‘brats’, as the junior pupils were called, he was bullied by the older boys at Stonyhurst and eventually a friend of the family intervened to persuade his father to move both boys to a gentler school.

In 1857, then 20, Alexander sailed back to India with his father – comparative strangers to each other. They arrived to discover the country in a state of rebellion. Indian sepoys – infantrymen for the East India Company – had mutinied against their British colonial rulers and the trouble spread across many of the northern states.

Alexander volunteered as an interpreter, accompanying the soldiers and playing an active part in quashing the rebellion. He put his life at risk on several occasions, earning plaudits from military commanders for his bravery.

“My Dear Gray,

I have much pleasure in testifying to your gallant conduct in our little affair near Chougien… and consider that had you been in the Military Service the Victoria Cross would undoubtedly have been awarded to you.

Yours truly H. W. Ryall, Commanding 3rd Sikh Cavalry, Buxar, January 14th, 1858.

Diamond hunting

Alexander’s next trip was to Rome, where his Scottish kilt attracted much interest and earned him an audience with the Pope! Then to the Middle East, where he was attacked and robbed in the Holy Land. He visited Iraq, Iran (where he met the Shah but was unwell and had to excuse himself to vomit) and Syria. He travelled again to India and then into China, before returning to Scotland and settling for two or three years.

In this time he met Marcella. She had been born in Jamaica, the daughter of sugar planters. Alexancder married the 20-year-old in May 1867. In 1868 news broke of a discovery of diamonds in South Africa.

“Wanderlust seized me once more and made me desirous of seeing a new part of the world – and I also hoped to have the pleasant occupation of finding diamonds.”

His wife was keen to join him. It was a successful venture. The diggings ground belonged to a Boer Dutchman called De Beers. Alexander paid £50 for the rights to dig one claim of 30 square feet, finding many diamonds there, including a 40-carat yellow diamond worth £400 (over £40,000 in today’s money).

He bought more claims and hired dozens of locals to dig for him. One of these claims cost him £25. He sold it some months later for £1,000 (over £100,000) to take a tour of the African interior with his wife, before returning to Scotland.

What glimpses we have of Stella suggest she had character. Asked by an African woman once how many oxen he’d paid for his wife, Alexander said “three”. The woman replied: “She says you paid six!”

Brief return to Scotland

They arrived back in Scotland in the summer of 1875 and it seems that soon after Alexander was off again – to Borneo, to hunt for more diamonds. He stayed with Dayak headhunters, sleeping in a room beneath 40 to 50 skulls of enemies they’d captured, “dangling sufficiently low to be within reach when I stood up.”

Here he first demonstrated a trick that was to serve him well on later travels – with his false teeth:

“Astonishment is a mild word to express the wonder produced when, by apparently pressing first on the stomach, next on the chest, I made it appear that I was thereby able to bring up an entire brigade of teeth from my inner man…”

In Borneo Alexander narrowly escaped with his life when the boat he was in overturned in a storm. From here he went to Burma (Myanmar), hunting for rubies and then to Thailand before heading home to his wife again, via Singapore.

Pregnancy

In November 1876, six months pregnant, Stella joined Alexander on a much less tortuous journey, but just as influential. They visited Caunton, the home of Samuel Reynolds Hole, one of the founders of the newly formed Rose Society and its president. Hole’s roses may have been dormant, but that trip fuelled a shared passion for Tea roses. Sadly, just three months later, shortly after giving birth to Alister, Stella was dead.

With a young child to raise, Alexander become absorbed with roses, though he couldn’t suppress his wanderlust completely – family legend tells that he would leave his son in the care of the butler and housekeeper while he went travelling. And though his experience at Stonyhurst may not have been entirely happy, he clearly thought something of it, sending Alister there to be educated.

In 1885 he moved from Dunkeld in the Highlands to the less rugged climate of Bath, where he bought a large house. It had been built in 1772 by Governor John Zephaniah Holwell, a survivor of the Black Hole of Calcutta. Maybe that connection to India is what drew Alexander to the place.

He paid £3,000 for the house, coach house stable, gardener’s cottage and several parcels of garden.

His garden had a steep rocky slope and he employed nearly a hundred men to terrace it. He had to import 150 tons of virgin soil , 200 tons of rotten turf and apply 1300 tons of cow, pig and horse manure for the beds. To this he added ‘hoof parings’, brewers’ grains (or ‘brains’ as the young Alister called them), boiled bones, guano and even – at one point – putrid horse flesh and some dead pigs! He eventually planted 10,000 roses in the garden.

With the help of his faithful gardener, Alfred Young, he set about growing, showing and breeding roses. He won the Tea-rose trophy for amateurs 14 times at the National Rose Society’s Show in London. “Amateur” seems a generous definition given the resources he had at his disposal!

‘Alister Stella Gray’ rose

‘Alister Stella Gray’ was introduced in 1894 – a repeat flowering Noisette hybrid rambler. It is often described as deep buff, but when I’ve seen it – at Sissinghurst late in the season (as in the picture at the tope of this page) – and in New Zealand, it is the young buds that are buff. The flower fades to creamy white. It came from seed he found in Jersey. Paul’s roses in Cheshunt propagated and sold it.

And what of the boy it was named after – by this time a 27 year-old? Newspaper reports show that the year the ‘Alister Stella Gray’ rose made its debut in rose catalogues, father and son were planning a long Autumn trip together to the south of Spain to collect more seeds.

For the last 30 years of his life Alexander would retire to his island home at Santa Maria in the Azores in the winter, enjoying his roses at Beaulieu in the summer. He wrote many articles for the Rosarian’s Year Book about his visits to rose gardens there and around Europe. His wanderlust never went away completely.

Grim collection

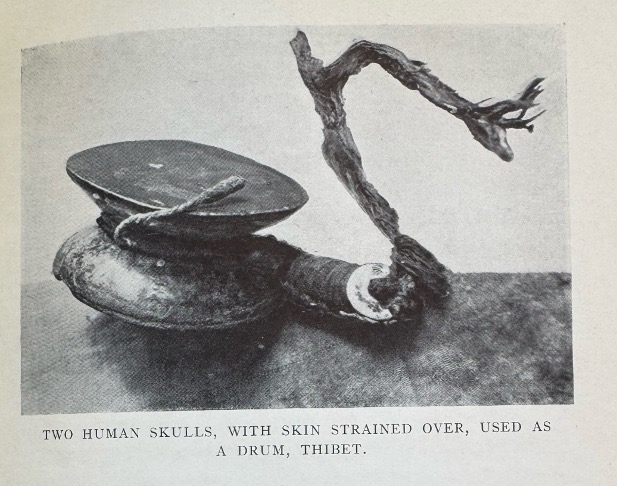

Alexander died in August 1927, aged 90. He left a collection of thousands of souvenirs from his earlier adventures, including blowpipes and poisoned arrows, trumpets made of human thigh bones, a bamboo piano from Bangkok, and drinking cups fashioned from human skulls.

His body was carried back to the Highlands and he was buried alongside his wife, his son Alister among the mourners. Alister , like his father, married a Marcella Kerr – his cousin. In 1928, following his father’s death, he and Marcella sailed for Jamaica where he worked on the family’s sugar plantations. He died in 1957, aged 80.

I hope Alister appreciated this rose, which is still sold today – and bears the name of the two most important people in his father’s amazing life.