Who was Mme Hardy?

Félicité Hardy lived in the shadow of her famous husband, but 150 years after his death, she is the one remembered today, thanks to the rose he named after her.

Julien-Alexandre Hardy (1787-1876) created the popular 19th century French rose, ‘Mme Hardy’, in 1831. The Revue Horticole described it for the first time the following April, which explains why many rose catalogues date it to 1832.

Hardy was head gardener at the Jardin du Luxembourg in Paris. Research by my old friend, French garden historian Vincent Derkenne, suggests he originally named it ‘Félicité Hardy’. The rose only became known as ‘Mme Hardy’ in the 1840s.

Courageous florist

Sadly, much more is known about Alexandre than Félicité. He was the son of a gardener and began working for a florist in Paris at the age of 15, before being admitted shortly afterwards as a gardener apprentice in a nursery on the outskirts of the French capital.

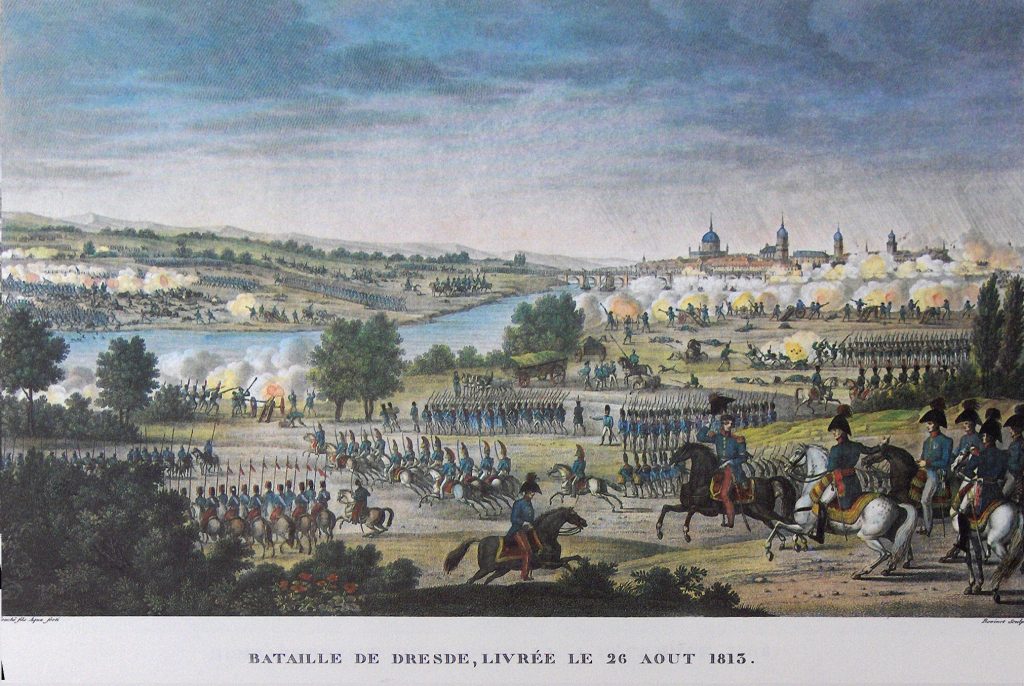

In 1806, when he was 19, Alexandre served in Napoleon’s army in the Spanish and Portuguese campaigns. He was wounded at Dresden in 1813 and nominated by the Emperor as a Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur. He was demobilised on the Emperor’s abdication the following year.

In 1816 he won a job as under-gardener at the Jardin de Luxembourg. There he became quickly familiar with André Dupont’s collection of roses and many more. Within a year he had earned promotion to head gardener, a post he held till 1859. Roses and fruit trees were his lifelong passion.

Teaching

Alexandre was clearly charismatic – it is reported that he would deliver free early-morning lectures on the pruning, grafting and planting of fruit trees and gather a large crowd of gardeners to listen. And in April 1832, reporting on the latest new roses, the Revue Horticole pays particular attention to him and his rose garden.

“The Luxembourg rosarium, constantly tended with the rarest taste and intelligence by Mr Hardy, was visited every morning by a large number of ladies, curious onlookers, and amateurs, who came to admire the colours, the most graceful and varied forms, and to savour the fragrances of this multitude of roses, whose selection and collection attest to Mr Hardy as the most passionate, enlightened and favoured lovers of flora. This rosarium contains only the beautiful and the very beautiful. It is here that young rose lovers should go to develop their taste and seek advice, in the most kind manner of Mr Hardy, to plant at home collections of roses worthy of their admiration.”

Félicité

But what of Félicité? She was born in December 1790 and christened Marie Thérèse Félicité Pezard. Her uncle was a well-known nurseryman, Michel-Christophe Hervy, who was director of an important fruit tree nursery neighbouring the Jardin du Luxembourg. He and Alexandre became friends. We can assume that it’s at the Hervy’s house that the impressive young gardener met Félicité.

Romance bloomed and on 5 March 1818 Félicité and Alexandre married in the church of St Sulpice in Paris, moving in to live with the Hervys. Alexandre and Félicité went on to have three children of their own – Eugène (1819-54), Alexandrine (born 1820 but died in infancy) and Auguste-Francois (1824-91). Auguste-Francois followed in the family footsteps, becoming director of the École National d’Horticulture at Versailles.

‘Mme Hardy’

The rose named after Félicité only blooms once a year, but as Graham Thomas said, it is “one of the most superlatively beautiful of the old white varieties… having few peers among the coloured varieties.” He describes a “suspicion” of flesh pink in the half-open buds, and comments on the green eye, which makes this rose so distinctive.

The great Victorian rosarian, Samuel Reynolds Hole, thought that green eye a drawback – associated with jealousy – but most people see it as part of its charm. If there is any jealousy to be connected with this rose, it is the envy it must trigger among others that cannot match its charm.

Félicité died on 26 May 1846, aged 55. Her husband lived another 30 years after her but never remarried. She is buried in the cemetery at Montparnasse in Paris with her son, Eugène, and Alexandre.

Dying first meant that, on their tombstone at least, she got top billing over her husband, “Mr Hardy”.

With thanks to Vincent Derkenne for his assistance with this blog