When gardeners planted bomb shelters

Visiting the extraordinary Longest Yarn 2 exhibition recently, which tells the story of WWII in knitted and crocheted panels, I spotted Anderson shelters in some of the woolly gardens.

There were still quite a few of these around when I was growing up in the Northeast of England, 30 years after the war.

The Anderson shelter was a feature of many wartime British gardens – 3.5 million were installed between 1939 and 1945. Martin Stanley is one of a handful of people to still have his today.

Pictured above, it sits in his garden in Vauxhall, London, covered in daffodils in springtime. He opens it to parties of school children and historical groups.

The Anderson shelter was a cheap corrugated iron shed, designed to offer householders at least some protection during air raids. It was named after Sir John Anderson, who was responsible for civil defence during the war, and designed by an engineer, William Patterson.

Dig for safety

Householders would dig a pit – typically about 4 foot (1.2m) deep, 6.5 feet (2m) long and 4.5 feet (1.4m) wide and line the floor with wood or concrete.

Then to the shelter. Think of it like a metal tent. You bolted together six curved corrugated panels – three either side, joining them at the top to create an arched structure (about six feet high). You then fastened the end plates – one with a door opening – and fitted the whole thing snugly into your pit.

Growing veg on top

A lot of the soil you had dug out for the pit then went over the top – minimum 15 inches (38cm) deep. You now had a half-buried shelter that was particularly strong against the compressive force of a nearby bomb. And you could grow food crops on the roof. Rationing and the Dig for Victory campaign meant there was an impetus to make use of every square foot of garden for vegetables and fruit.

Though most Anderson shelters were six-panel, built for six people, some were four and others 10. Martin’s is a 10-panel shelter – the owner of the house was a builder who had access to concrete so made a good job of it. The corrugated panels were issued free to anyone earning less than £250 a year (in today’s money that’s about £14,250). For anyone else they cost £7 (£400). The government also provided instructions on how to install bunk beds so you could sleep in the shelter during a raid. Or at least be a little bit comfortable. They would have been extremely cold, dark and damp, perhaps waterlogged and probably claustrophobic. And you would have heard the bombs.

“Shelters like ours were fairly habitable,” says Martin. “You wouldn’t want to spend a lot of time in them, but they weren’t horribly unpleasant. But shelters that were just set in the ground in soggy London clay would have got quite miserable.”

Lifesaver?

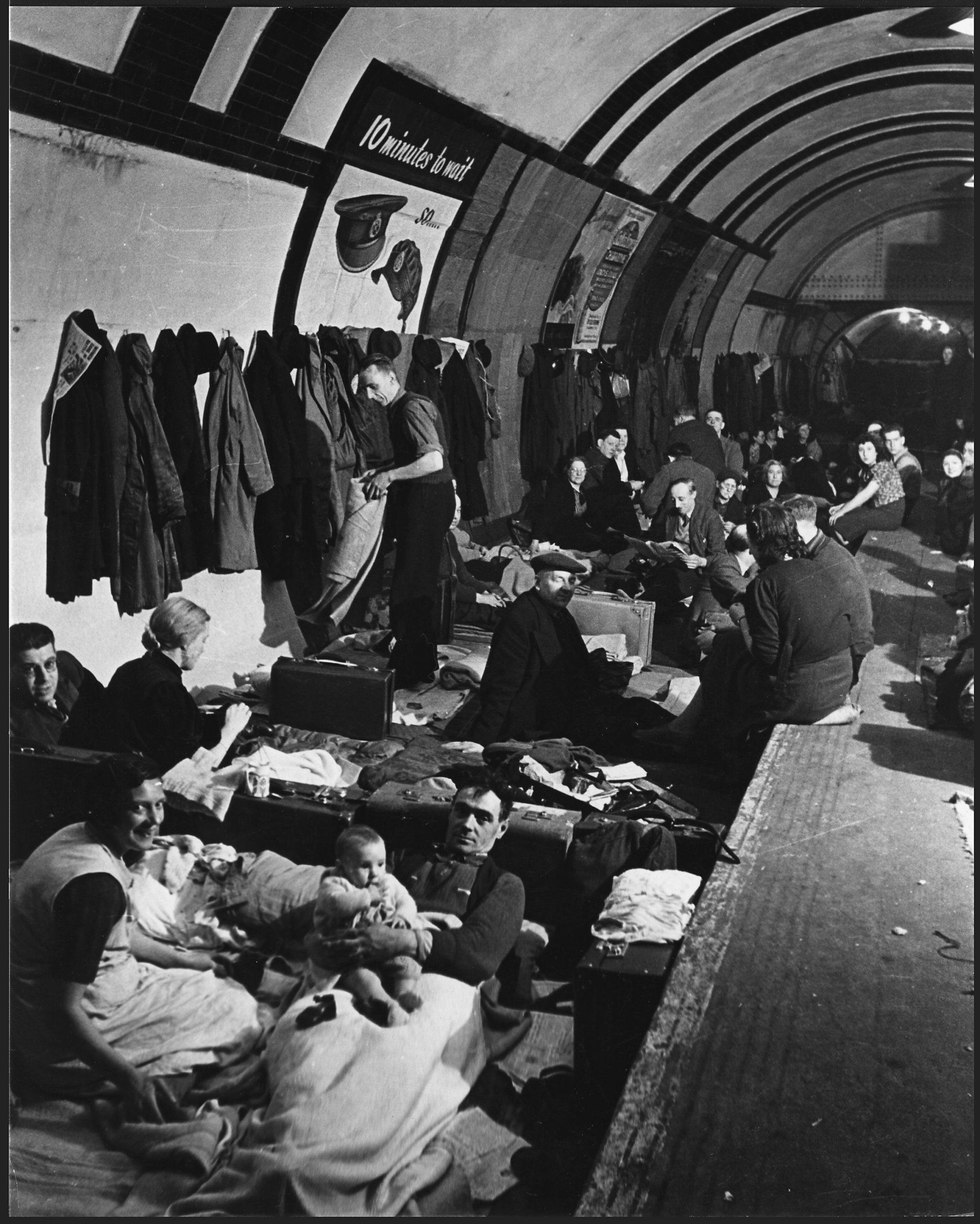

Of course, you also had to have a garden to instal them in. So middle-class households were much more likely to benefit than others. Some may have shared their shelters with neighbours. But this is why so many people in London went to the underground railway stations for safety instead.

Did the Anderson shelter save lives? They may have been safer and were initially popular, but people soon tired of the discomfort. Government scientists found that in British cities just over half of families did not or could not take shelter. By November 1940 only around 27% of Londoners used them regularly. For some a fatalistic view set in that if a bomb “had your name on it” you were done for anyway. Some might call that bravely stoic. Perhaps it was mental self-preservation. For many it was fatal.

It is estimated that during the war 220,000 homes were destroyed or so badly damaged that they had to be demolished. In the nine months of the German aerial blitz, between September 1940 and May 1941, 41,480 people were killed. The terrace of 12 houses that Martin lives on has gaps at each end where homes took direct hits.

He says: “We live in an area that was heavily bombed. When I point this out to the children, it makes them stop and think.” He says the children usually identify one other aspect of the shelters that will have put many off. “They are not impressed by the spiders!” he jokes.

Survivors

After the war the government collected up many of the shelters it had given away, though people would be offered the chance to buy them for £1. Some would refit them above ground and use them to store garden tools. Others left them buried and raised mushrooms or forced rhubarb in them. Today, Martin estimates there are about 15 Anderson shelters like his, half buried, left. Why has his survived? “We bought the house about 35 years ago and it was fairly derelict. It needed a lot doing and we kind of ignored this thing in the garden because we were so busy. The architect told us it would cost a lot to get rid of and we didn’t have the energy, or probably the money either! But over the years we’ve grown quite fond of it. We’ve realised it’s quite special.”

They may not have been comfortable. They may not have been as readily available as they should have been. But Anderson shelters did save lives. Those like Martin’s that remain are reminder of a terrifying time when gardens provided not just vital food, but also shelter and safety.