Constance Spry – David Austin’s first rose

Constance Spry was not actually Constance Spry. And for someone whose fame lay in the seemingly sedate world of flower arranging, she was in many ways shockingly radical.

She never married the man whose surname she took. And for four years of that relationship had a passionate gay affair. Meanwhile, she transformed the floristry world by adding kale leaves and tree branches to her vases and built a business empire that spanned both sides of the Atlantic. What a woman!

Few people have ever demonstrated such creative flair and irrepressible energy. Her influence lives on in flower arranging today, and in the name of the first – and still one of the best – roses that David Austin created.

She was born Constance Fletcher in Derby in 1886, the youngest of six. Her father, George, was a gifted teacher. In 1901 he moved the family to Dublin to work as a senior inspector for the Department of Agriculture and Technical Instruction, rising to become Chief Inspector of Technical Education in Ireland.

Early love of flowers

Clearly, he had a good garden, which seemed – Spry later wrote – “always to have been bathed in sunshine and filled with flowers.” She spent most of her weekly pocket money on seeds, but though she “picked the flowers, climbed the trees, and ate the fruits,” she “learnt nothing at all about how to grow them.”

The family’s gardener, Mr Fox, had a treasured well-matured stack of stable manure that the children were not allowed near. It took on a magical mystery quality to Constance. She yearned for a trowel full in which to grow her penny packet of Viginia stock.

One day she decided to procure some for herself, hiding in a clump of elder bushes by the road with a toy dustpan and brush, waiting for a passing horse to unburden itself. Quickly, she dodged the dangerous wheels of the carriages to retrieve her prize.

“I made a triumphant dash, flourishing my dustpan”, she said. But her antics were spotted by a passer-by, and she was given such a strict reprimand that:

“It made me inhibited against the use of manure for the rest of my life. If only my wise and understanding father had been at home at that moment, this incident would have been turned into a wonderful lesson about plants and soils, and the comforting, cleansing processes of nature.”

Educator

Maybe that experience helped inspire her to become an educator herself and – ultimately – to write at least 13 books on gardening, cookery and flower arranging.

Her first job after training in London as a health lecturer, was setting up mother-and-baby clinics in Ireland. Constance, like her father, proved a natural teacher. She was soon overseeing a team of four health lecturers.

Her job took her from village to village. In April 1910, while lecturing on nutrition, cookery and first aid in County Kilkenny, she met mine manager James Heppell Marr. As women did in those days on marrying, she gave up her job.

It was an abusive and miserable marriage. In March 1912, they had a son, Anthony, but it did not help. Throughout this time, Constance sought solace in the garden. She laboured to tame a wilderness and began teaching herself to grow flowers, fruit and vegetables.

At the outbreak of WW1, Marr joined the army. Constance returned to Dublin to assist her friend, Lady Aberdeen, in setting up a branch of the Red Cross.

Spry

In 1917 she moved to England to become welfare officer at an armaments factory and was quickly promoted to Director of Women Staff at the Ministry of Munitions in London. This gave her income and independence. And an introduction to a man who was to become a big part of her life – her boss, Henry ‘Shav’ Spry.

Despite him being married, they began an affair. By 1923, Constance had divorced Marr and moved in with Spry. She took his name, even though there is no record they ever wed. He could not bring himself to divorce his wife.

Constance began working as head of the Homerton and South Hackney Day Continuation School, amidst the slums of London’s East End. She campaigned for social reform and education, and meanwhile, ever energetic, started a side hustle arranging flowers for dinner parties of friends and colleagues.

As a child, and only daughter, Constance’s job had been to “do the flowers” for the table. She wrote;

“I realise that a large proportion of these ‘creations’ may have had merit as barriers during family arguments, but as beautiful arrangements they can have had little or none; there were, I fear, just grotesque.”

Breakthrough

Practice seems to have made perfect. In 1927, the businessman Sidney Bernstein attended a lunch party at Constance’s home and was so impressed by her garden and arrangements he commissioned her to provide flowers for his Granada cinema chain. At the same party, the designer Norman Wilkinson asked her to arrange the flowers for his scent shop in Bond Street.

“Unconsciously, I think, I had struck a moment when people were getting tired of the conventional set pieces made by professional florists….”

Constance’s arrangements were made up of what she called ‘weeds’. They included brambles, kale, yellow yarrow, lichen-covered branches and hedgerow blooms. They were dramatic and stopped passers-by in their tracks.

“Requests for flower arrangements came in thick and fast, and I decided to embark on a small shop…. a thing [that] would not have been tolerated in my younger days.”

She was 43 when she opened her first shop in Marylebone in London.

“I was too nervous to take a chance and embark on a shop in a really good location, and took instead a small one in an out-of-the-way place. To intending shopkeepers I would say, never do this. Financially it is fatal.”

Gluck

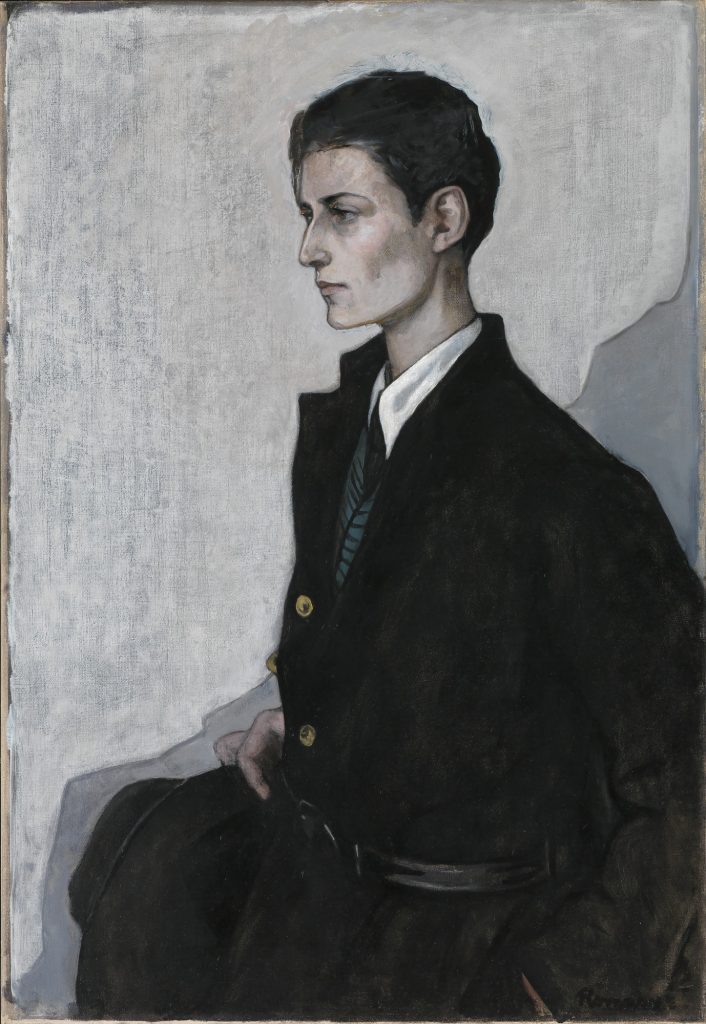

Though not in Constance’s case. She kept the shop for several years and still attracted interesting commissions. In the spring of 1932, she was asked to send some flowers to the Hampstead studio of the celebrated artist, Hannah Gluckstein, who was known as Gluck.

Gluck was pleased with the white arrangement and painted it. Constance was intrigued and decided to visit to see the painting herself. A passionate affair ensued that only ended when Gluck met and fell in love with someone else four years later.

Royalty

In 1934, Constance opened a shop in a much more prominent location – 64, South Audley Street, in Mayfair. Despite Constance now living with Gluck, she retained the support of Shav, who had retrained as an accountant. He had begun to rein in Constance’s financial indiscipline – many of her projects went over budget. He’d also begun a relationship with her shop manager. Civilised and convenient.

From this new shop Constance began to build a celebrity clientele and attract the attention of royalty.

In 1937 Wallis Simpson, commissioned her to arrange the flowers for her wedding to the former King, Edward VIII – a marriage that scandalised the nation because the American was a divorcee. Shock, horror! He abdicated the crown in 1936 to be with her.

Later, Constance arranged the flowers for the wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip. At Elizabeth’s coronation in 1953 she not only designed the flowers for Westminster Abbey but also put on a feast for 350 foreign dignitaries, with her friend, Rosemary Hume.

They created a new recipe in the Queen’s honour for the occasion, which they published in the hugely popular “Constance Spry Cookery Book”. That recipe was “Coronation Chicken”.

Flower school

Education was a constant thread through Constance’s life. In 1934 she had opened a flower school in London. She lectured in the US and on the eve of WWII – unfortunate timing – set up a shop in New York, too.

In 1946 Constance and Rosemary opened the Constance Spry Cordon Bleu School of Cookery in London, which later became a residential women’s school of cooking, gardening and home decoration, at Winkfield Place near Windsor.

Constance had spotted the dilapidated Georgian mansion in ‘Country Life’ Magazine. Though 60 at this point, she was determined to renovate and use it. In this she had the support of ‘husband’ Shav (they had come back together after the Gluck affair ended). On the curriculum were lessons in ‘Home Decoration’ and ‘Needlework skills’. The place needed plenty of both. Successive groups of pupils were put to the task – and charged 100 guineas a term for the privilege.

“Of one thing I feel sure, a working knowledge of both gardening and cooking would tend to give a young woman in the inevitably difficult world of tomorrow, an added confidence about living, a talisman in times of stress and a reassuring sense of independence and power.” – Constance Spry

Penny Snell, was one of her floristry pupils. She learned to do her own accounts, to grow her own flowers and condition and arrange them. She later had her own business and did large flower arrangements for the Victoria and Albert Museum for many years.

So what was Constance like? Penny tells me:

“She used to come in and out and there’d be a lot of hushed: ‘Oh! Mrs Spry’s upstairs!’ They invited me to work in her flower shop in South Audley Street, and it was the same reverential atmosphere there. But she was very friendly – quite shy, I think. I earned £5 a week, which just about covered my train fares. I was downstairs in the workroom making decorations. I had to be there from 7am and didn’t get home till 7pm.”

“And what did you think of her as a flower arranger?” I ask.

“Oh, wonderful. When people think of Constance Spry these days they think of triangular arrangements but it was not like that. They were free-flowing and wild. She would go and pick cabbage leaves and cow parsley and sticky buds from the horse chestnuts – anything that took her fancy.”

“And what was she like as a person?”

“If she bought herself a twin set of pearls she’d probably buy ten and then give nine of them away to various friends. She was very generous to her friends – not to staff but to her friends! She was very demanding of her staff. At Winkfield for instance, she’d go and sit in her bed writing her books at the dead of night and her staff would be crawling on their hands and knees below the glass panel in her bedroom door because they didn’t want her to see them going to bed while she was still sitting up. I expect she thought they should still be slaving away.

“Her students did the place up, didn’t they? That’s quite savvy!”

“Oh yes, she had all her buttons on, I tell you! She had enormous energy and thought everyone else should have the same amount of energy. We decorated the Royal Opera House when the Shah of Iran came. We all had to knuckle down to make dresses out of carnation petals for all those maidens around the dress circle. They were sewn individually onto a muslin base. We didn’t even get a word of thanks but it was a marvellous experience. No extravagence was spared. They brought in complete apple trees covered in blossom. It was fabulous and great fun. She was a one-off.”

Roses

Constance’s great passion – or one of her great passions – was old roses. Graham Stuart Thomas claimed that by the time of her death at Winkfield in 1960 she had built one of the best collections of old roses in Europe. She also helped save many from extinction.

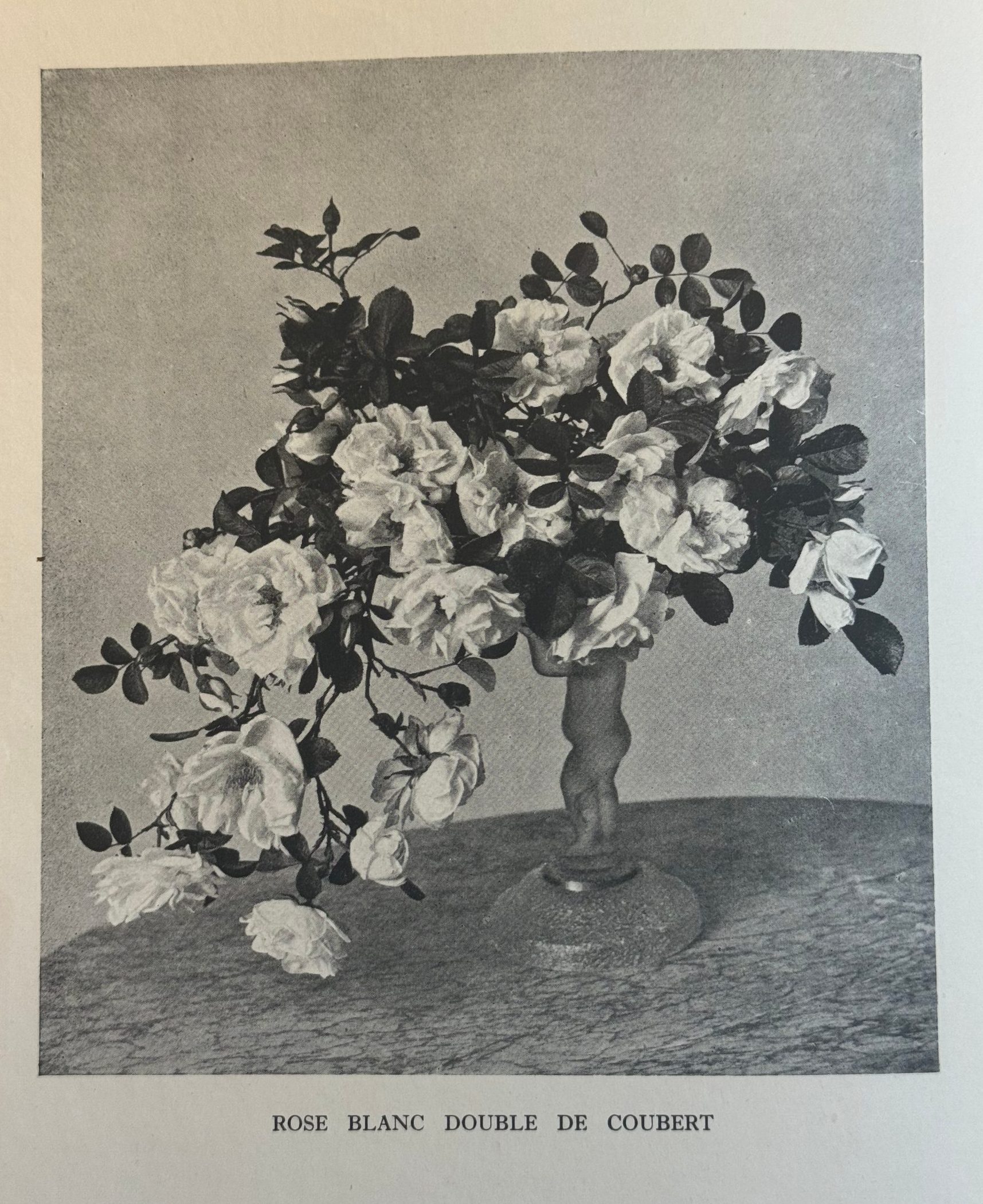

She lists 41 in her 1940 publication, “Constance Spry’s Garden Notebook”, describing many in detail. They include ‘Blanche Double de Coubert’, ‘Charles de Mills’, ‘Commandant Beaurepaire’, ‘Hippolyte’, ‘Salet’ and ‘Village Maid’ – all grown by her friend Vita Sackville-West, too. (And still grown at Sissinghurst today.) She writes:

“These names are enough; either you will want to possess all of them and many others that you find described in old rose lists, or you will be bored. You may in any case think I have written with undue enthusiasm and ridden my hobby-horse too hard; but it does seem to me that these roses, which are so vigorous, so hard, and so foolproof, might be grown in many gardens instead of in the very few.”

‘Constance Spry’ rose

A year after her death, David Austin named his first rose after her. ‘Constance Spry’ is the first of his ‘English roses’. It is a cross between the 1845 Gallica rose, ‘Belle Isis’ (the seed/ovule parent), and the 1940 Floribunda, ‘Dainty Maid’ (which he used as the pollen parent).

Though it only flowers once, it is still one of my favourite roses – an abundant climber, with a strong myrrh fragrance. In flower, it bursts with energy, just like its namesake.

Though for many Constance Spry is now just the name of a popular rose, there are some who still see her influence in the horticultural world.

Enduring influence

Shane Connolly was commissioned to design the flowers for the Coronation in 2023. He was also guest curator of an outstanding exhibition on Constance Spry for the Garden Museum in 2021. He says:

“She was an extraordinary person. Women in her day did not do what Constance Spry did. They didn’t set up a business; they didn’t very often leave an unhappy marriage and start a new life; they didn’t train in the way she trained – as a health educator – during the First World War. And they didn’t keep a business going for the rest of their life, employing a lot of people and empowering… [other] women to continue in that vein.”

He says she changed perceptions of home making and was a precursor to celebrities like Sarah Raven and Martha Stewart – women who have made home making into an art. And he sees her influence on his own career.

“I was lucky. I trained at Pulbrook and Gould, which was a complete descendant of Constance Spry. Rosamund Gould was Spry’s right hand lady. Lady Pulbrook was Spry’s client. They started up a rival business in 1956.”

Inspiration

Shane encourages people to buy and read Constance Spry’s early books.

“These are the ones that show how great her brain was and they’re brilliant. These are the ones you can use… I still do, especially if I’m puzzling and thinking: ‘What can you do that would be shades of red?’ She’s got something to say about it.”

“So you’re still a fan?” I ask him.

“Oh, yeah. Totally!”

Me too, now. And the rose? It may only flower once but it is one of my favourites. If I ever had to downsize to a garden with just 10 roses… perish the thought… I think this would have to be among them.