Dahlia mania, Keynes and an unusual party at Stonehenge

John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946) is one of the most influential economists in history. But there’s a strong case to be made that he owed his expensive education and status to a 19th century flower craze – “dahlia mania”.

Let’s travel back to Wednesday 31 August 1842 and to Stonehenge. Beneath the towering megalithic stones are clustered a series of tents and as many as 10,000 visitors.

A brass band is playing and 160 gentlemen are sitting down to a dinner. For once, the central attraction of the show is not the prehistoric architecture but a “Grand Exhibition of Dahlias” and the man at the centre of it all is Keynes’s grandfather.

John Keynes (1805-1878) was the Honourable Secretary of the Salisbury Plain Dahlia Society. He had only recently started his nursery business but had been a keen dahlia grower and breeder for some time. He recognised the value of the flower in adding colour to the late Summer and Autumn garden. And in making him money.

From here on he regularly advertised his tubers in the newly-established Gardeners’ Chronicle and became known as one of the principal grower of dahlias in Britain at the point when the craze for the flower was at its peak.

Dahlia mania

The dahlia had only arrived in Europe in 1788. It came from Mexico where it was grown 5,000 feet above sea level on sandy plains in what is now Mexico City. This was once the capital of the Aztec empire. The Aztecs ate the tuber root as food (as they did potatoes). They boiled the root as a diuretic, cough treatment and to reduce fever. They used the hollowed stems of some dahlias as pipes, and the stems of the tree dahlia (D. imperialis) – which can grow to 20 feet – for carrying water.

The first European to get his hands on dahlia tubers was Antonio José Cavallines. He was a leading Spanish botanist at the Royal Gardens in Madrid. When it flowered the next year he named it after the Swedish botanist Anders Dahl, a pupil of Linnaeus who had died a few months earlier.

Europeans saw no value in the dahlia as an edible crop and Beeton’s 1871 All About Gardening suggests they were not that impressed with its then single flowers either:

“Under the impression that sandy soil was its proper compost, it lingered in our gardens, a miserable scraggy plant, till 1815, when a fresh and improved stock was introduced from France and it was taken up by florists.”

Dahlias do not grow true from seed – they naturally hybridise. By the turn of the 19th century nursery owners had realised this and begun to hybridise for particular traits – colours and shapes. The first double dahlias began to appear in Europe around 1805. And slowly gardeners began to appreciate it. By 1830 there were over 2,000 varieties of dahlia in cultivation and 14,000 by the 1930s. Today there are 57,000 different cultivated varieties registered with the RHS.

Dahlia mania

The Salisbury Plain Dahlia Society was formed in 1838 to organise al-fresco celebrations of the flower for the local gentry. That same year, Joseph Paxton, head gardener at Chatsworth and a co-founder of the Gardener’s Chronicle (he was an extraordinarily energetic man), wrote a “practical treatise on the cultivation of the dahlia”. In it he extolled the flower’s virtues:

“I shall not be guilty of a departure from the truth when I say, that it is at present by far the most interesting, beautiful, and popular autumnal-flowering plant, of which the gardens of this country can boast.”

You can tell how popular these exciting new plants were by a letter from the poet Wordsworth to a friend about this time. In it he objected to how people had abandoned treasured natives, like hollyhocks, in favour of imported ‘plants and flowers’. He expressed his regret that “the Dahlia and other foreigners recently introduced, should have done so much to drive this imperial flower out of notice”.

Keynes was not complaining. He had the instincts of a showman. In 1837, at the Salisbury Royal Dahlia Show, he had earned the “universal and unmingled admiration” of visitors with an “at once novel and highly ingenious” display, described by the Salisbury and Winchester Journal:

“It consisted of several thousand dahlias so arranged as to represent a large and splendid piece of drapery, on which appeared the word “Victoria” in white, antique-shaded letters; above this was a brilliant star, and the whole was surmounted by a magnificent imperial crown…”

He repeated the trick at the first Stonehenge show in 1842. This time with an award-winning display of the coat of arms of the Antrobus family on whose land Stonehenge sat. And in 1845 – the fourth and final Stonehenge dahlia show – he seemed to surpass himself, “presenting Flora in a Car drawn by four swans”. All in dahlias!

It’s incredibly frustrating not to be able to see images of these. Even after the Stonehenge dahlia shows finished, he was still wowing audiences with his creations.

“The most conspicuous object viewed from the lawn was the device formed of dahlias, place over the garden front of the mansion – a triumphal car drawn by butterflies – that was beautifully conceived and charmingly executed by Mr Keynes…”

– The Salisbury and Winchester Journal reporting on the Salisbury Grand Horticultural Fete, 29 August 1846

Change of plan

Keynes was not always meant to become a nurseryman. He had been apprenticed at the age of eleven to his father’s brush-making factory in Salisbury. But he caught the gardening bug early in life. Family legend says that one day, as a teenager, he was on a stagecoach from Salisbury to Andover and was captivated by a purple carnation (Butt’s ‘Lord Rodney’) in the buttonhole of a fellow passenger. In that moment he determined to cultivate his own carnations and pinks. He pawned his watch to buy his first plants. He won his first show prize at the age of 17 – a pair of sugar tongs! This was 1823. But it seems he continued working in the family business, growing and showing flowers in his spare time.

Even as late as 1837 he was competing in flower shows as an amateur. Though clearly a successful one. But by 1840 he had begun to call himself a nurseryman and professional. The Gardeners’ Chronicle adverts show he was touting a bulb catalogue from at least 1841. The business thrived even beyond dahlia mania, which was comparatively short-lived.

Roses

A visitor to Keynes’s nursery in 1866 said his dahlias looked “splendid, but there was a lamentation over the falling off in support, owing to the bedding mania”. Garden tastes had moved on. And Keynes, too. By this time he had become just as famous for growing and selling roses. His visitor in 1866 noted how he was budding up as many as 2,700 ‘Marechal Niel’ plants – a rose only introduced a couple of years earlier. Glued into the cuttings scrapbook of the great Victorian rosarian, Samuel Reynolds Hole, is an article from the Gardeners Chronicle of 1867 where Keynes is praised for winning first prize for a box of 48 roses at the first Western Rose Show.

This is a man who knew how to adapt. The money he made he reinvested shrewdly, buying land strategically around Salisbury needed for the new railway line being built there.

Death

A staunch baptist – John Keynes was for many years also the Sunday school superintendent of Brown Street Baptist Chapel in Salisbury. He was a big advocate of education and helped build a school in the cathedral city. He was much loved there, serving as a Liberal councillor and – in 1867 – as mayor.

On his death from stomach cancer in 1878 most of the shops in Salisbury closed for his funeral. Soon after, the Keynes’ family interest in his nursery were sold. He left assets worth over £40,000. That’s the equivalent of over £4m today. Not bad for someone who had turned a hobby into a living!

His son John Neville Keynes became an economist at Pembroke College, Cambridge and, helped by the wealth he inherited, ensured his own children had the best possible education. John Maynard Keynes pursued his grandfather’s other hobby – investing. He made a fortune trading commodities but lost it in the crash of 1929. He changed tactics and in time recovered his fortune, meanwhile becoming famous as one of the most influential thinkers of the 20th century.

But perhaps none of this would have been possible without the craze for dahlias, and the passion of an extraordinary grower that financed his family’s education and privileged lifestyle.

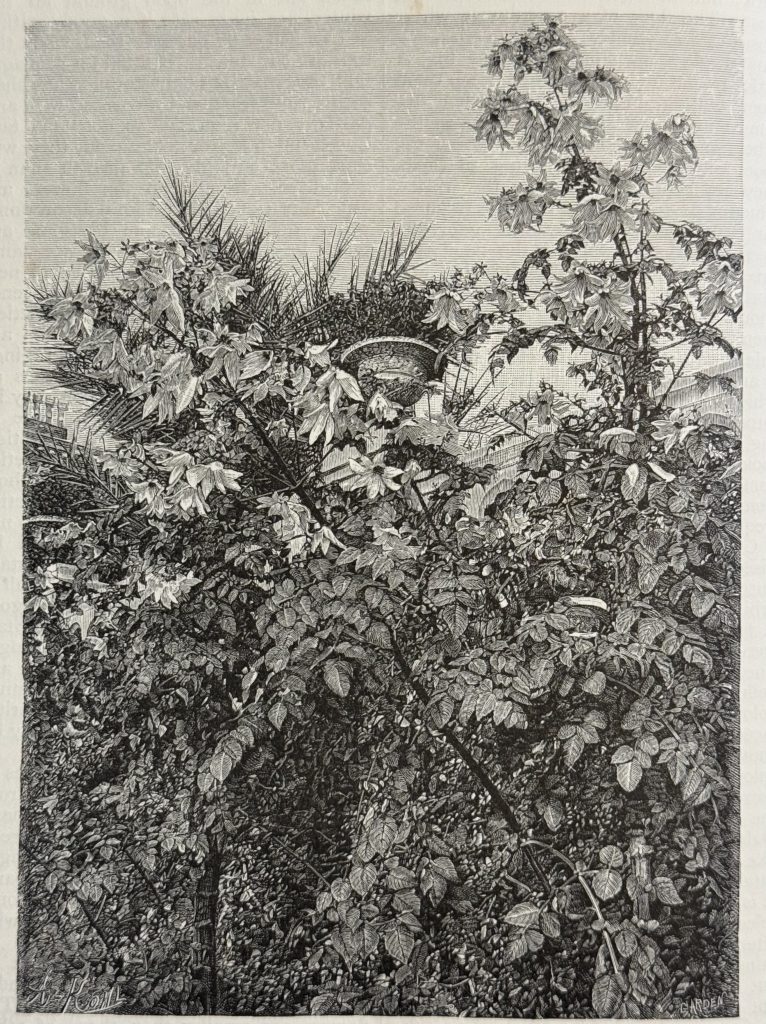

Top image: Dahlias at Great Dixter. Copyright: Martin Stott, the Storyteller Garden