The ‘Peace’ rose – celebrating 90 years

There it is in the yellowed hybridisation notebook of rose breeder Francis Meilland – the record of what he later called “the first pollen-charged brush stroke” that led to the birth of the world’s most popular rose, ‘Peace’.

The 23-year-old Meilland scribbled the entry on 15th June 1935. His family tell us it reads:

“3-35-40: ‘Joanna Hill’ x Semis (‘C. P. Kilham’ x ‘Margaret McGredy’)”

The numbers showed that it was the third combination made in 1935 and the 40th of the 50 most promising seedlings that Francis and his father, Antoine, had shortlisted that year from at least 800 produced. These 50 would be transplanted to the trial beds. The names were the parents of the new rose as Francis remembered them.

Shaky start

Years later he would write: “It was not very sturdy, this little 3-35 plant, and there was nothing about it to attract attention.” But over the next four years the Frenchman, who had been aiming for a copper coloured rose with disease resistant foliage and winter hardiness, watched the seedling in the field. Gradually he began to appreciate its unique qualities.

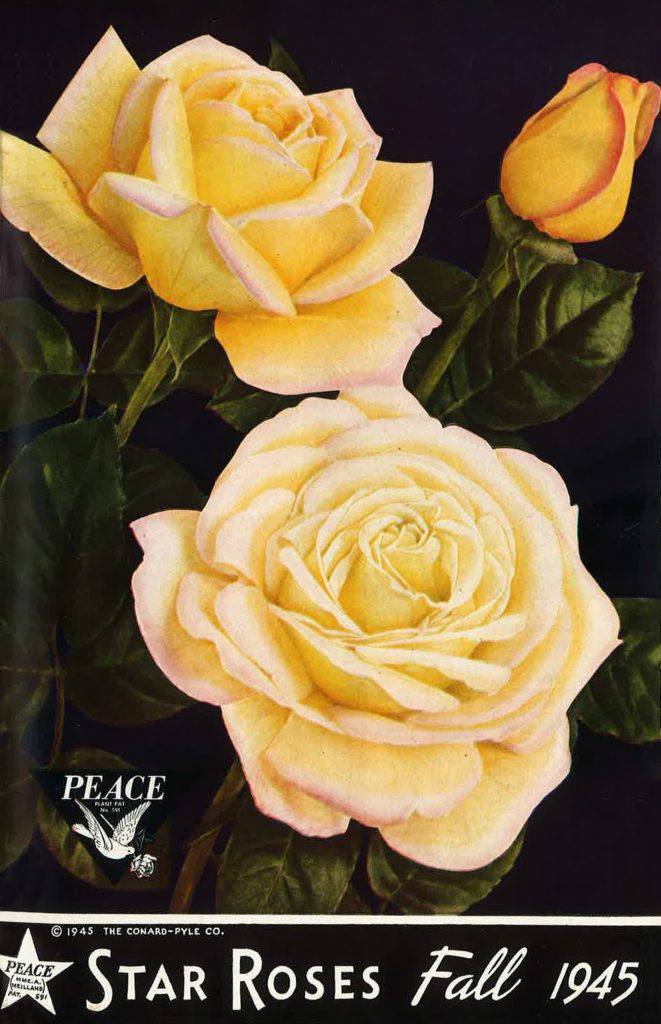

In June 1939 with the world hurtling towards war again, Francis decided to invite some of his best international clients and rose friends to the Meilland nursery in Tassin-la-Demi-Lune in the south of France, near Lyon. One rose caught everyone’s attention that day. It carried on its stems the label ‘3-35-40’. It bore large, faintly-scented blooms of yellow, fringed with pink, and had high-centred buds and glossy foliage. Those visitors were transfixed.

Three months later, on 1st September 1939, Hitler invaded Poland. The following May he began his assault on France. Francis had managed to post two small parcels of propagating wood of 3-35-40 to his friends in Italy and Germany before the Germans attacked. English rose breeder Jack Harkness later claimed he’d sent some to the US, too, but Francis was uncertain whether the parcel had arrived.

At first the Germans occupied only Northern France. The collaborationist Vichy government governed the south. But in November 1942 Hitler decided to extend his occupation to the whole country.

Frantic despatch

As the Americans were shutting up their consulate in Lyon and preparing to leave, the rose-loving vice-consul, George Whittinghill, phoned Francis. He offered to take messages from the Frenchman to his friends in the US, and even a parcel, so long as it weighed no more than half a kilo. Francis had just two hours to get the package over. He moved quickly, managing to rush some carefully wrapped propagating wood to the consulate. It included 3-35-40 and was addressed to the legendary American nurseryman, Robert Pyle. This time Francis knew it would arrive.

The plane took off. A few hours later German troops and tanks crossed into what had been the Unoccupied Zone.

It was to be many more months before Francis was to hear what had happened to his rose.

Liberation

A month after the liberation of France he received a letter from Pyle. It read:

“Whilst dictating this letter, my eyes are fixed in fascinated admiration on an enormous canary yellow rose, with carmine-edged petals; there it is, majestic, full of promise. And I am already convinced that it will become the grandest of the century.”

He was writing about 3-35-40.

Pyle had tested the rose in his own trial beds and sent it to other rose-growing friends across the US. From the feedback he had received he knew it was a winner.

In France, Francis had christened the rose ‘Mme A. Meilland’, after his mother, Claudia, who had died a few years previously in her 40s. In Italy it was being marketed as ‘Gioia’ – Joy. In Germany his friends were selling it under the name of ‘Gloria Dei’ – Glory of God.

Pyle was a marketing genius. The rose still had no name in America, but he persuaded the American Rose Society to organise a christening at the Pacific Rose Society’s Exhibition in Pasadena, California on Sunday 29 April 1945.

‘Peace’

As the American film actress, Jinx Falkenburg, christened the rose ‘Peace’, two doves were released into the Californian sky. At that very moment the Russians were in the streets of Berlin. His capital effectively lost, Hitler killed himself the next day. The war with Germany was over.

Meanwhile, a conference was taking place in San Francisco, where representatives from 50 countries were drafting the charter for the United Nations. Pyle had had the brilliant idea of placing a bloom of ‘Peace’ in every delegate’s bedroom.

Not so easy! Security was tight and the authorities refused to allow it. Pyle was undeterred. He discovered that the only people allowed in each room were the hotel bell boys. He bought 300 small vases and made his own clandestine arrangements, paying the boys $1 a bloom to deliver a vase to each room, containing a cutting of ‘Peace’ with this message:

“This is the Peace Rose which was christened at the Pacific Rose Society Exhibition in Pasadena on the day Berlin fell. We hope the Peace Rose will influence men’s thoughts for everlasting World Peace”.

Awards

On August 15th 1945, the day the Japanese announced their decision to surrender, American rose judges gave the prestigious All-American Award to ‘Peace’. On September 2nd 1945 the American Rose Society gave the rose its supreme award – the first time a newcomer had been awarded the accolade. That was the day a peace treaty was signed in Japan.

‘Peace’ went on to secure honours across the world. It was the first rose to win a place in the World Federation of Rose Societies’ Hall of Fame in 1976. It was sold in the UK from 1947 by another great rose showman, Harry Wheatcroft, who became Meilland’s great friend and agent. During the 1950s the rose dominated competitions here. So successful was it, some local horticultural societies reportedly had to create a separate class for ‘Peace’ in their rose show schedules to give others a chance.

Influence

On its 80th birthday, Meilland estimated that more than 100 million ‘Peace’ roses had been planted around the world. And the rose had appeared in the bloodlines of at least 382 roses since the 1950s.

It was influential in another way too. Robert Pyle had used America’s patent laws to licence production of the rose in the US. It meant he was able to profit from the rose’s success, and so were the Meilland family. The money they made helped them re-build the business in Antibes after the war.

Francis worked tirelessly to get similar legislation in Europe. He created his own international organisation, Universal Rose Selection, for the creation and distribution of his roses under license. In time the laws were changed. Rose breeders would be fairly rewarded for their patient endeavour.

Francis was a force of nature, but in 1958 he became seriously ill. He was sent to Paris to see a specialist. When he and his wife, Louisette, arrived in the waiting room a bouquet of ‘Peace’ roses was in a vase on a table. Francis stared at it. He later told Louisette that it was not just the flowers he saw but, standing alongside them, the mother he had named them after.

He died in June that year. Antonia Ridge, in her book, For the love of a rose’, records how his friends and neighbours all stripped their gardens of ‘Peace’ roses. As his body was laid to rest in the cemetery at Antibes, Francis’s coffin was strewn with the rose he had created. The world’s most popular and influential rose.