Pirates, spying and the discovery of weigela

The cold-blooded Chinese pirates are closing in with murderous intent and adventurer Robert Fortune knows his life is in peril. It’s 1845 and the Scotsman is attempting to reach the island of Chusan in a hired Chinese junk. From there he will sail to Shanghai then back to England with a cargo of precious plants he’s been collecting for months. But first he must stay alive!

Fortune had spent the past few days trapped in his cabin recovering from fever. He thought the crew were being alarmist when they warned him about the pirates who infested the area. But the junk hasn’t sailed far when it comes under attack. Groggily, he looks out on the deck and sees the crew lifting planks, trying to hide any valuables from the raiders. They have changed into rags, knowing the pirates will hold for ransom anyone deemed wealthy.

Returning fire

As the pirates start firing broadsides on Fortune’s junk, the terrified crew flee to hide below deck. Furious, he takes out his gun and threatens to kill the last two sailors still at the helm. He commands them to stay put to keep the boat on course, then turns his guns on the enemy.

“While the pirates were not more than twenty yards from us, hooting and yelling, I raked their decks fore and aft, with shot and ball from my double-barrelled gun. Had a thunder-bolt fallen amongst them, they could not have been more surprised. Doubtless, many were wounded, and probably some killed. At all events, the whole of the crew, not fewer than forty or fifty men, who, a moment before, crowded the deck, disappeared in a marvellous manner; sheltering themselves behind the bulwarks, or lying flat on their faces. They were so completely taken by surprise, that their junk was left without a helmsman; her sails flapped in the wind; and, as we were still carrying all sail and keeping on our right course, they were soon left a considerable way astern.” – Robert Fortune Three years’ wanderings in the Northern Provinces of China

All this to bring some new plants to our nurseries in Europe!

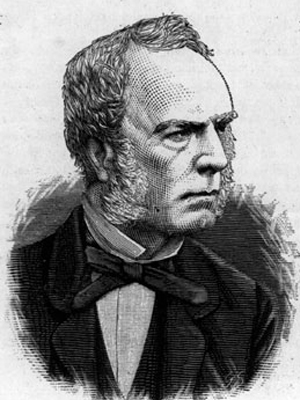

Botanist Robert Fortune (1812-1880) was perhaps the most successful of the 19th century plant hunters. In three trips to China between 1843 and 1847 he sent back in wardian cases as many as 250 plants, including this week’s featured plant, weigela.

Working undercover

For centuries China was closed to Western travellers. After The Opium Wars China was forced to open several ports to British merchants. In early 1843 Fortune was commissioned by the Horticultural Society (the forerunner of the Royal Horticultural Society) to take advantage of this to go looking for undiscovered plants.

Even given China’s submission to the British Empire’s gunship diplomacy, this was no easy task. As a Westerner, Fortune often attracted large crowds – and pickpockets.

With Imperial hauteur, he described his technique for escape:

“I walked on towards the hills and began to ascend them – a plan which I always adopted when I wanted to get away from the Chinese, as they are generally too lazy to follow far, where much exertion is required.”

Some might say the observation equally applies to the British today, as anyone will testify who has fled the crowds swamping Bakewell in Derbyshire on a Bank Holiday by the simple expedient of heading out to the hills and away from the pie shops.

Fortune faced danger many times. At one point he was violently robbed, escaping narrowly with his life. Several voyages almost ended in disaster because of incredible storms. And often he had to travel in disguise. No Westerner was allowed more than a day’s walk from the treaty ports. So when travelling illegally in the interior he wore a shaved head and ponytail, pretending to be a traditional Chinese merchant.

Tea espionage

Fortune, who also travelled to Japan, was responsible for discovering many plants on these trips that are found in gardens today. They include forsythias, lilacs, winter jasmine, skimmia japonica, several varieties of rhododendron, honeysuckle, clematis and peony. He also introduced at least half a dozen roses. His most famous accomplishment was smuggling nearly 20,000 tea plants and some skilled tea makers out of China to India. By doing so he made possible the Indian tea industry, estimated today to be worth over $11bn a year.

Weigela

Fortune had visited the island of Chusan (between the Chinese mainland and Japan) a year before the pirate attack. It was there that he came across weigela in the garden of a Chinese mandarin. He considered it one of the most beautiful shrubs of Northern China.

Fortune had visited the island of Chusan (between the Chinese mainland and Japan) a year before the pirate attack. It was there that he came across weigela in the garden of a Chinese mandarin. He considered it one of the most beautiful shrubs of Northern China.

“It was loaded with its noble rose-coloured flowers, and was the admiration of all who saw it, both English and Chinese.” – Robert Fortune Three years’ wanderings in the Northern Provinces of China

After Japan was opened to Westerners several other species of weigela were discovered by Westerners. Part of the honeysuckle family, they are a native of Eastern Asia. They’re named in honour of the German scientist, Christian Ehrenfried Weigel (1748-1831).

I have just returned from three weeks visiting gardens in Japan. To see weigela in the wild there is to be reminded of how exciting it must have been for Fortune and other European planthunters to discover these plants for the first time. Today we take them for granted.

Hero of villain?

More than 170 years after those noble flowers won admiration in that Chinese garden, I cannot help feeling similarly about the two pretty weigela cultivars in my own. There’s a variegated pink, and a dark crimson. I have more mixed emotions about Fortune.

He was a product of his time – colonial racist, a horticultural thief and an industrial spy. However, in breaking the Chinese tea monopoly he created a huge industry that still benefits India today. Maybe without him the English would not be so obsessed with drinking tea. Our gardens are certainly immeasurably the richer for his efforts. Hero or villain? Probably both.