Where do clematis come from?

Today’s plant offers us a wealth of stories, involving pilgrims, cricket, planthunters, a Virgin Queen and gonorrhoea! And it all started with me being curious enough to wonder: “Where do clematis come from?”

There are over 300 species of the clematis genus (maybe as many as 400). Of these 147 come from China. Many are found in southern Europe and North America, Planthunters have discovered others in the Carribean, Australia and West Africa.

Aged whiskers

The UK has just one wild clematis – C. vitalba. This was a common cottage garden plant before more and better varieties were introduced. It has several common names, including ‘Traveller’s Joy’ and ‘Old Man’s Beard’.

Gerard credits himself for coming up with the name ‘Traveller’s Joy’ in his herbal of 1597. It was found in the chalky south-eastern part of England and on the road pilgrims trod from Gravesend in London to Thomas à Beckett’s shrine at Canterbury.

“…decking and adorning waies and hedges where people travell, and thereupon I have named it Traveller’s Joy”.

It has no medicinal purpose, he claims, though that is not true of all clematis. Scientists today are interested in its potential uses for modern drugs. Parts of the plant have been used in Chinese traditional medicine as a diuretic, antidysentery and to treat rheumatic pain, fever, eye infections, skin disorders, gout and gonorrhoea. So a handy plant to have around!

But it was its beauty and scent that was C. vitalba’s main attraction for Gerrard. It gave pleasure as did the “goodly shadow” it cast – welcomed perhaps by pilgrims seeking some respite from the sun on their journey.

“Old Man’s Beard” refers to the clusters of feathery fruits that follow flowering in autumn. These whiskers are decorative in their own right and enhance the value of the plant in the same way as rosehips enhance roses.

Tudor introductions

The 16th century saw other introductions to England. Queen Elizabeth’s apothecary, Hugh Morgan (c.1540-1613), introduced C. Viticella from Southern Europe in around 1569.

A bell-shaped late flowerer, its common name is “Virgin’s Bower”. It was intended to convey a compliment to “The Virgin Queen”. Historians (mainly male historians to be fair) have spent far too much time arguing over whether Elizabeth was actually a virgin, but she liked to foster the fact that she had sacrificed any chance of love for the kingdom, so I hope it’s a compliment she appreciated.

Gerard grew a second clematis – C. flammula (meaning ‘small flame’) – which must have arrived some time before 1597, therefore. A white clematis with a heavy scent, it comes from Spain. Gerard claimed that if you crush the leaves on a hot summer’s day “it causes a smell and pain like a flame”. He called it Purging Periwinkle.

C. cirrhosa, (which Maggie Campbell-Culver memorably describes as sounding “like a disease of the liver”) is another Tudor introduction. A slightly tender evergreen, it is said to have been discovered in Spain by the Dutch botanist, Carolus Clusius.

Right: Clematis rubella and marmorata

From Moore & Jackman’s “The Clematis as a garden flower” 1827. Copyright: Martin Stott, Storyteller garden.

Asia

One of the most popular clematis groups is the Montana Group. Its members descend from a Chinese or Himalayan species, C. montana, discovered in 1802 in Nepal by Francis Buchanan (1762-1829). Buchanan was a Scottish surgeon with an incredible array of interests. He’s listed as a botanist, pteridologist (studies ferns – yes, I needed to look it up too), zoologist, ichthyologist (nothing to do with scratching – it means he studied fish), physician, ornithologist, naturalist, geographer and malacologist (someone who studies molluscs).

Buchanan’s career began as a ship’s surgeon sailing back and forth between England and Asia before he settled in India. He returned to Scotland in 1815 through ill health and became the official keeper of the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh. He is listed as having collected 485 different plants on his travels in India, including several types of clematis. Buchanan’s C. montana first flowered in Europe in 1805.

by The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London. Creative commons licence

The end of the Opium Wars opened up China to exploration and from the 1840s planthunters, like Ernest Henry Wilson began to explore the country and more clematis were discovered. C. montana var. wilsonii has creamy-white flowers and a strong scent of chocolate!

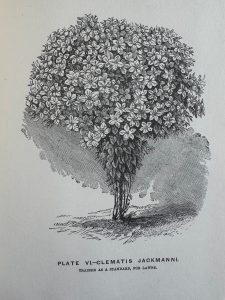

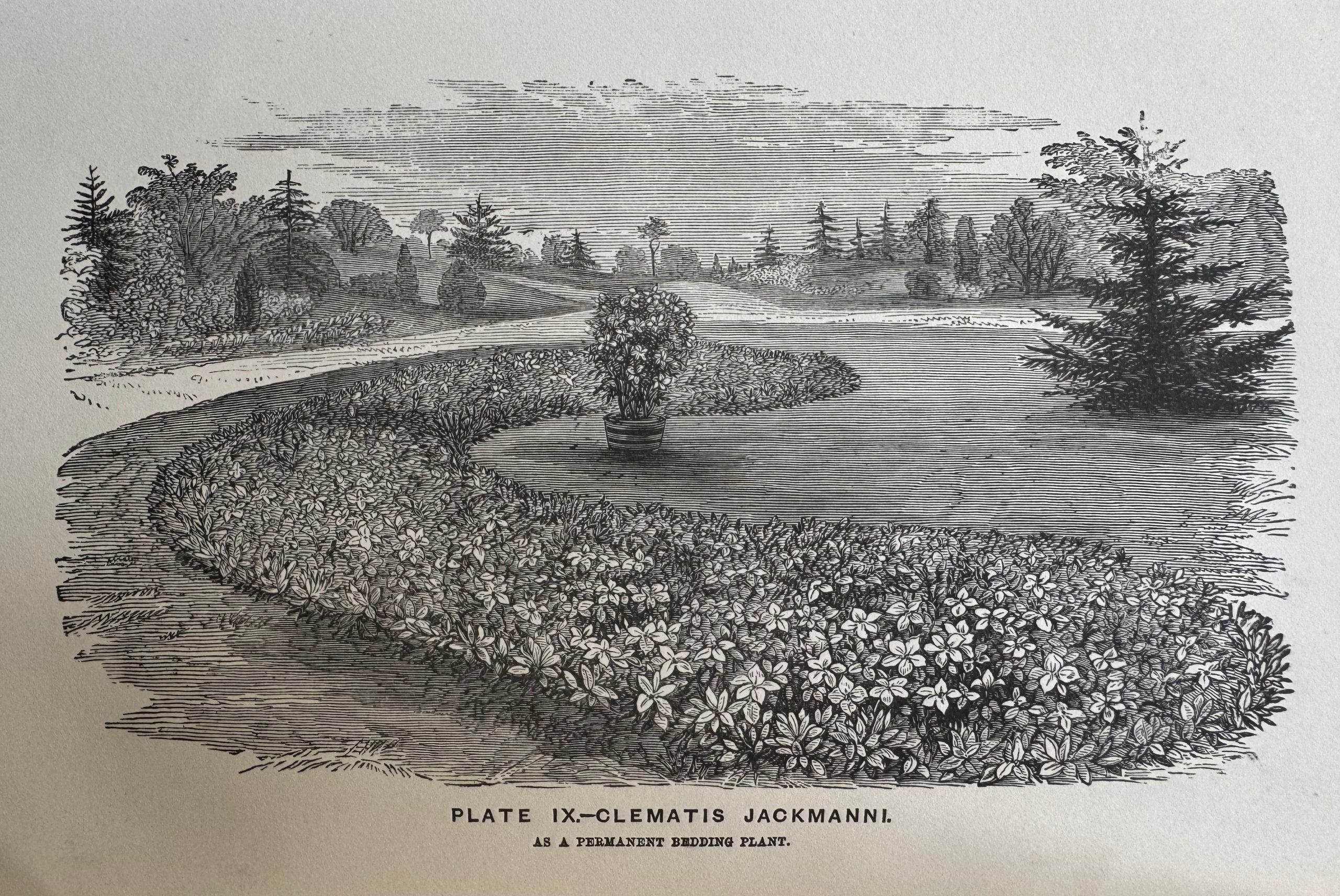

As an unusual bedding plant

The word ‘clematis’ comes from the Greek word for vine or tendril, and refers to its climbing habit. But gardeners do not have to have them wending their way up walls, pillars and posts.

Writing in 1877, Thomas Moore and George Jackman highlighted the potential of clematis as a bedding plant. Yes… laid horizontal. They got the idea after an accident at Jackman’s nursery in Woking.

Some clematis seedlings he was hybridising were blown down one early summer and their supports were not replaced. The Jackman nursery was a huge affair, employing 35 men and six boys across a 90-acre site, so it’s not surprising, perhaps, if the job got forgotten. They tell us:

“As the summer and autumn passed on it was noticed that these plants spread out their branches over the surface of the ground and flowered as profusely there as when elevated in the usual way.”

The gardeners learned if they pegged the clematis down like this – planted two feet apart and overlapping – they made a good permanent bedding stock that flowered year after year with increasing vigour. During the winter, when the beds are bare and bald Moore and Jackman recommended moving in pots of evergreens like Aucuba japonica and Berberis Aquifolium between the permanent plants to give some interest.

This seems a fantastic idea to me – environmentally friendly and pretty low maintenance. I’d love to see someone (with a bigger garden than mine) try it. I think it would look particularly nice on a sloping bed with cyclamen providing the winter interest, perhaps.

Clematis Jackmani

The clematis Moore and Jackman recommend as a bedding plant is the lovely purple C. jackmanii – still widely available. It was produced by Jackman in 1862. C. jackmanii is considered the first of the modern large-flowered hybrid clematises, though it wasn’t the first to be successfully hybridised. That honour goes to a deep bluish-purple clematis, C. hendersonii, bred by Edward George Henderson at his nursery in St John’s Wood, London in 1835. This plant is also still available today and I may now have to get one.

Incidentally, Lords Cricket ground now stands on the site of what was Henderson’s “Pineapple Nursery”. So, when you hear Test match commentators say: “The bowler’s running in from the nursery end…” think of Mr Henderson and his clematis!

George Jackman (1837-1887) later used C. hendersonii in creating his own eponymous masterpiece.

But that’s enough for today. This is a plant we’ll come back to again another time, I’m sure.